(Source: Getty Images)

(Source: Getty Images)

My husband, clowning around in the pre-stolen Rush hoodie

My husband is a huge Rush fan, and has been since middle school, 35 years ago. For those of you who aren’t Rush fans, or aren’t intimately acquainted with one, it’s hard to describe the passionate devotion these fans have. As I learned more and more about this band, it became clear to me that this devotion doesn’t spring from the music alone. Although their music is exceptionally well-crafted (it’s tough to find a rock musician who doesn’t acknowledge Rush’s truly exceptional talent and skill), there are innumerable excellent musicians out there. What makes Rush stand out is their heart– the way this trio of hardworking men treat each other, the way they treat their fans, the way they treat their families, protecting them from public scrutiny. Their humility, sincerity, self-effacing humor, and quiet generosity stand out in an industry that often rewards arrogance, selfishness, and self-aggrandizement.

Neil Peart, Geddy Lee, and Alex Lifeson of Rush. Source: avclub.com

I’ve written before about “geniuses” behaving badly because we enable that kind of childish behavior, and Rush stands as a constant reminder that genius and assholicity don’t necessarily go hand in hand. Most drummers consider Neil Peart to be the greatest rock drummer of all time. For you fellow classical nerds out there, he’s like the Liszt of rock drumming– he’s written things only he can play, things other drummers have to find ways around. Yet he leads with humility and graciousness, not braggadocio, arrogance, and self-aggrandizement. All three are like this (the other two are Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson)– brilliantly skilled and startlingly humble, far more apt to make a self-effacing joke than brag about their accomplishments or gifts.

It is impressive.

So as my husband introduced me to Rush, I began to understand what he adored about them, why they were, after all these years, still so close to his heart, so close to the hearts of millions.

In 2012, my husband took our teenage son to his first Rush concert. It was the Clockwork Angels tour. It was huge for my husband, as you can imagine. At the tour he bought a hoodie that quickly became his favorite. He treasured it.

Then, in 2016, the Year of Everything Awful, my husband, on the way home from work, stopped to duck into a pub to say hello to a few fellow middle school teachers for just a moment. He couldn’t stay, but he thought he should at least make a quick appearance at the gathering. He was gone for less than ten minutes. In those ten minutes, in broad daylight on a busy suburban street at 4:30 in the afternoon, someone smashed his car window and grabbed his school bag (containing nothing but student paperwork) and his beloved Rush hoodie.

The smashed window.

We have insurance, and the school bag had nothing in it that couldn’t be easily replaced. I sighed and went online immediately to the Rush website to replace the hoodie. It was nowhere to be found. I then checked every website and did every google search I could think of. I checked eBay. I was willing to pay double by this point. All I wanted was to replace this hoodie my husband loved so much. I had no luck.

My husband is a very humble man who hates to cause trouble, so I knew my next step would have to be behind his back. Believing that someone within the Rush organization must have some of these hoodies in a box in a warehouse somewhere and would be willing to sell one to me, I tracked down several people within the Rush organization I believed might be connected to merchandising, and told them our story, asking them if there was any way I could still purchase this hoodie. One of the people I contacted was a man named Brandon Schott.

Within a few days I had received an email from a woman named Pegi Cecconi. I did not know who she was and did not think to google her. Brandon Schott had forwarded the email to her, commenting that I seemed “sincere.” Pegi Cecconi, as it turns out, is the Vice President of SRO Management. Her .sig does not give her title, and I was too much of a Rush neophyte to understand how far up the chain she was until I told my husband, who promptly freaked out.

Pegi had forwarded our email to Showtech, the merchandisers, and personally asked them to help us.

Soon, a man named Alex Mahood contacted me. They didn’t have the Clockwork Angels hoodie, but they had one like it, and they would send it right over, free of charge. Soon, we received a box with this hoodie in it.

The man in the new hoodie.

I had offered to purchase the hoodie in every email I sent them, yet they sent this to us as a gift.

They could have easily ignored my emails. They could have easily just said, “Sorry, sold out.” They could have turned to more important things– they all have far, far more important things to do. Yet they chose kindness and generosity.

It is impressive.

Rush has a song called “Closer to the Heart” that says we can create a better future for each other by approaching our work, whatever that work is, closer to the heart.

2017 is an uncertain year for people all over the world. People are feeling anxious, frightened, and helpless. They see open hatred increasing all around them. They fear for the future. There is only one way to respond to this: Everything we do from this point forward needs to be closer to the heart.

We must take care of each other more now than ever, and this experience gives me hope. I understand replacing a stolen hoodie isn’t equivalent to saving a life or fighting for justice, but the impulse comes from the same place. It’s the impulse to lead with love and to take care of those around us, and we must, now more than ever, take care of those around us.

Not every important action will be earth-shattering and felt by thousands. Sometimes working for a better world is one tiny, unseen act. Listening and believing instead of dismissing and arguing. Hearing the truth of someone’s lived experience with an open heart and mind instead of acting defensively and angrily. Holding space for grief and pain instead of policing the way that grief and pain is expressed. Taking a moment to understand that our experiences and beliefs are not “right” or universal. Taking a moment to understand that difference can be celebrated rather than feared. Taking a moment to see the humanity in each other.

Sometimes we take care of each other by standing against racism and homophobia, robber barons and oligarchs, zealotry and hatred. Injustice. Hunger. Greed. Selfishness. And sometimes we take care of each other in small, personal ways. They are all important.

Yes, 2017 is here, and many are frightened, but we are not helpless. Every day, you can lead with love and act closer to the heart. Every day you can work for justice. Every day you can recognize the humanity in others. Every day you can reach out your hand to help someone, in large ways and in small ways.

Maybe it’s silly for a single hoodie to give me hope. Maybe, maybe not. But I have hope in others. I have hope in you. Live 2017 closer to the heart.

Happy New Year.

(And thank you, thank you, thank you Brandon Schott, Pegi Cecconi, and Alex Mahood. <3)

Remember when Gamergate was happening? All those online attacks, threats, and harassment by the “alt right” pretending to be about “ethics in games journalism” but really just attacking, threatening, and harassing women and people of color for discussing the portrayal of women and people of color in video games? And everyone was like, “Oh; it’s just a minority of people doing that– just a fringe group” and “Well, some of them really do care about games journalism,” and “It’s just online harassment. Just ignore trolls!”?

Now people connected with the “alt right” are going to be in charge of the government. The man who was one of the unofficial heads of Gamergate, Milo Yiannopoulos, writes for Steve Bannon, at Breitbart “News.” Steve Bannon, Trump’s White House Chief Strategist, supported Yiannopoulos throughout the entire Gamergate debacle, and (just before his leave of absence to work for Trump) through the massive sexist and racist attack campaign Yiannopoulos led against Leslie Jones, the final straw that got Yiannopoulos kicked off Twitter because he finally attacked someone with enough fame and power to get people to pay attention.

Even those within Gamergate who insisted throughout that it was about “ethics in games journalism” still defined those ethics as keeping cultural criticism out of gaming. As video games became more and more complex, creating scripts and animation to rival major studio films, games criticism began to include the kinds of artistic considerations we within the arts are well used to. Critics began to consider the social context of games in addition to their basic functionality, sometimes critiquing games for their sexist portrayal of women, or for their lack of diversity. Even if it were about “ethics in games journalism,” Gamergate was defining “ethics” largely as “never talking about sexism or racism in games.” This is an important point, as there really are ethical considerations in games journalism, all of which Gamergate completely ignored in favor of sending death threats to a woman who creates videos about sexist tropes in games and an independent female developer who wrote a free game about her struggle with depression, among others. The “alt right” movement Gamergate considered personal attacks, harassment, and threats an appropriate response to arts criticism— led in part by Milo Yiannopoulos while he was supported and employed by Steve Bannon, soon to be one of the most powerful men in the world.

One of the most important things to note about Gamergate is how often they threw around the term “free speech” to defend attacks, threats, and harassment meant to silence discussion around sexism and racism in the video game industry. One popular talking point at the time was the fact that Anita Sarkeesian had turned off comments on her video series critiquing the portrayal of women in video games, Tropes vs. Women, both on YouTube and on her website, Feminist Frequency, when the attacks, threats, and harassment began, which was characterized as an attack on their “free speech.” This is important to note– they felt so entitled to attack, threaten, and harass this woman that they claimed it was a violation of their free speech when she refused to personally create a space on her website for them to do so.

One of the most important things we can do as citizens is connect the dots between events. Steve Bannon paid Milo Yiannopoulos while he led attacks, threats, and harassment against people advocating for feminism and diversity AND claimed it was a violation of free speech when special space was not created for these attacks to occur. When Yiannopoulos was booted from Twitter for violating their ToS in leading the sexist and racist attacks on Leslie Jones, the movement howled that Yiannopoulos’ “free speech” was being violated. Bannon paid Breitbart writer Jack Hadfield to write an article for Breitbart claiming Yiannopoulos was a “free speech martyr.”

While women and people of color are the canaries in the coal mine of shitty American trends– if bad things are coming down the pike, they’re going to hit us first– it’s also important to note that Gamergate was, at its core, a fight over arts criticism. While people are quick to dismiss art as “just a game” or “just a movie,” art is where we, as a culture, decide who we are, who we want to be, what we fear, what we value. Art is where culture is made. So it’s no surprise to me that this “alt-right” movement in part coalesced and gained popularity around two movements angry about the inclusion of women and people of color in art and arts journalism– Gamergate for video games, and Sad Puppies/Rabid Puppies for SciFi/Fantasy.

Yet the response to these attacks and their alarming ideology at the time was a collective shrug of the shoulders. The most popular response was “just ignore the trolls.” This piece of advice could not have been more dangerously wrong.

We should have listened to women and people of color when they first began reporting these attacks. We should have responded robustly and clearly: No, this is wrong. Instead we shrugged our shoulders and told them, “Just ignore the trolls.”

We could have learned everything we needed to know about the “alt right” from Gamergate, and instead here we are, once again, telling each other to “ignore the trolls,” telling each other to discount Trump’s outrageous attacks on free speech when they’re on Twitter, as if they weren’t part of a larger world view that seeks to limit free speech (here, here, here, here, here), as if they weren’t coming from a man we’re about to put into the most powerful position in the world with Steve Bannon at his ear.

When Steve Bannon paid Milo Yiannopoulos to write articles that aided Gamergate and its horrific personal attacks against people who dared to openly discuss sexism and racism in the games industry, that should have been enough right there to make everyone terrified of handing Bannon any sort of political power. Now he’s about to have more political power– unaccountable political power, since he’s in an appointed, not elected, position– than nearly anyone else in the world, aiding a presumptive president elect who attacks free speech relentlessly. The “alt right” has openly fought against free speech for years. The question is, Have we learned anything from it? Or are we just going to keep saying “ignore the trolls”?

Source: Damon Winter/The New York Times

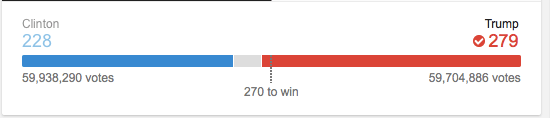

In a shocking upset over predicted winner Hillary Clinton, an open racist, sexist, antisemitic, Islamophobic, xenophobic, journalist-hating confessed sexual predator about to go on trial for racketeering has been elected president of these United States. There have been approximately infinity think pieces and news stories and nuggets of punditry discussing “what the Democrats did wrong” to lose this election. But here’s the thing: HILLARY CLINTON WON THE ELECTION. Democrats did nothing wrong. Clinton got more votes than anyone else running, which, in any other contest on the globe would mean she won. She lost the presidency on a bizarre and outdated technicality.

Journalists, pundits, and my fellow bloggers, the story isn’t “What did the Democrats fail to do?” it’s “Why do we continue to allow this antiquated ritual to deny the American people its democratically-elected choice for President?”

A majority of Americans wanted Clinton as their president, and due to a bizarre, outdated ritual, democracy failed them.

THAT’S THE STORY: DEMOCRACY FAILED.

What are we going to do about the fact that an antiquated ritual has (once again) robbed the American people of its democratically elected choice?

For all of you geniuses who thought Hillary was corrupt, you better hope you were right so she can move those levers of power, contact her rich Jewish banker friends, murder some people, or whatever your favorite Clinton fairy tale is, and get the electoral college eliminated before January 20. Since it would require a constitutional amendment (or at the very least the adoption of the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact in nearly all 50 states), she had better get cracking.

Obviously, it can’t happen before we all have to watch the candidate endorsed by the KKK sworn in to the highest office in the land. But we should get our act together and push for the elimination of the electoral college before it can do any more damage– and this isn’t even all the damage it can do. It won’t happen before Trump and Pence start dismantling everything that makes America great (or even livable), but it can certainly happen before 2020.

In the mid-60s, Jan Kott wrote a truly horrible book called Shakespeare, Our Contemporary, in which he analyzes Shakespeare’s plays according to his specific point of view as a white European male who hasn’t quite grasped the humanity of the women and people of color around him, although, at the time, we just called that “Shakespeare criticism.”

When discussing the character Desdemona, a character whose complete faithfulness to her husband is the primary narrative linchpin of the play, Kott says, “Desdemona is faithful, but must have something of a slut in her.” He says that she must be a slut “in potentia” if not “in actua” because so many men desire her– because she inspired erotic imaginings in the men around her. SO SHE IS THE SLUT.

And while this kind of “my white male imagination tells me so” Shakespeare “analysis” we’re used to getting from the likes of mid-century scholars like Kott (and Harold Bloom, and so many others whose “analysis” of Shakespeare’s female characters is 100% flights of fancy) it stood out to me, even as a teenager when I first encountered this nonsensical “analysis.” It stood out to me that THIS IS AN ADMIRED BOOK OF SHAKESPEARE CRITICISM. This was the first moment I realized that the world of academia was going to be an uphill battle for me as a woman.

This moment– seeing a respected book of lit crit describe male desire for a woman who never sought nor wished for that desire as HER OWN FAULT for somehow being a “slut” “in potentia”– has come to mind again and again this election cycle.

Millions of our tax dollars have been poured out in a desperate attempt to pin something, ANYTHING, on Hillary Clinton. Nothing illegal has ever been found. Every investigation has exonerated her, and the Clinton Foundation is one of the highest-rated on every nonpartisan site that monitors charities. Obviously false scandals have been created by alt-right (and regular right) propagandists, and they’re shared around the internet as if they make sense. Scandal after scandal have been manufactured and debunked. Hillary haters are the hydra of American politics– chop off one false scandal and two grow back. There’s a never-ending supply of false scandals, and the factual evidence debunking them is dismissed as “irrelevant” or “bought and paid for.” As if the Clintons have an unlimited supply of money– oh, wait, according to the Hillary haters, THEY DO, thanks to Jewish bankers and the Evil Jewish Scrotillionaire Necromancer Lich Demon George Soros.

Hillary haters are forced, in the face of all the evidence exonerating her, to claim that the lack of evidence is the evidence. What is she hiding? It must be something! LOOK AT ALL THESE SCANDALS. Anyone who points to the facts is “bought and paid for” with all Clinton’s Jewish banker money, something I’ve been accused of myself multiple times. (I only wish someone was paying me to blog.)

And so we come back to Desdemona. SHE MUST BE SOME KIND OF SLUT. LOOK AT ALL THESE MEN LUSTING AFTER HER, reasons Jan Kott. EVEN IF SHE’S FAITHFUL TO HER HUSBAND, he continues, SHE’S STILL A SLUT, OTHERWISE WHY WOULD OTHELLO BELIEVE IAGO? Why indeed.

Kott blames Desdemona for the scandalous thoughts men have about her, and we blame Clinton for the scandalous thoughts we have about her.

“She’s too heaped in scandal,” “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” “There must be SOMETHING there,” “She’s clearly corrupt,” “One of the most corrupt politicians ever.” We dressed her in this outfit against her will, then condemned her for it.

Kott goes on:

Othello does not have to kill Desdemona. The play would be more cruel, if, in that final and decisive moment, he just left her. . . . Othello kills Desdemona in order to save the moral order, to restore love and faith. He kills Desdemona to be able to forgive her; so that the accounts be settled and the world returned to its equilibrium. Othello does not mumble any more. He desperately wants to save the meaning of life, of his life, perhaps even the meaning of the world. (123)

Kott– a respected Shakespearean critic– writes that killing a woman falsely heaped with scandal is the only way to “restore love and faith” and “the meaning of the world.” That men must use women as scapegoats for their own dark desires and imaginings and then kill them to restore order. Only dead can women be forgiven for “making” men have dark desires. This, again and again, returns to my mind as I see so many respected people– elected officials– calling for the murder of this woman who has borne the brunt of their imagined scandals, the congealed crust of hate and fear of powerful, independent, outspoken women.

And now I type the requisite sentences, the ones demanded of everyone who writes about Hillary Clinton and no other politician, ever: Do I agree with her every decision? No.

But we cannot productively discuss what kind of president she will be (and she will be president) in reality while we continue to make her the scapegoated center of 1000 false scandals. We cannot have productive discussions about foreign policy or ed policy– two areas we really need to be discussing right now– while the country is embroiled in a non-scandal about emails, or an alt-right created one about sex (take your pick).

Jan Kott is still taught. And respected newspapers are still running stories about Hillary’s emails, and the entire GOP is participating in a false story about voter fraud and a “rigged” election. The question is: Are we going to continue the Kott-like misogynistic scapegoating of this woman, or are we going to get to work on the actual issues?

“Leap into the Void,” Yves Klein (photographed by Harry Shunk), 1960

When I write about diversity in representational media (theatre, film, TV, video games), often the white anger (and there is always white anger) uses “artistic freedom” as its battle cry. “Artists should create whatever they want, without restrictions,” or “Total artistic freedom is sacred. Telling artists they must include diversity is wrong.”

The secret is: Every professional knows there’s no such thing as “total artistic freedom.” We always must work within certain parameters. At least half of the artistic process is finding artistic solutions to technical problems.

The space you’re working in has physical constraints. The budget has limits. The contracts you’ve signed with the company, the playwright, the actors, the techs, all limit what you can add (or subtract) from the text, how long you can rehearse, even what can and cannot be done on stage. Props don’t work the way you imagined. An actor can’t perform the blocking you’ve set in the costume you approved. You discover three weeks before opening that the set you approved is over budget and needs trimming. The incredibly important piece of specially-designed tech hardware is stuck on a truck with a broken axle four states away and the earliest it will be in house is now Sunday afternoon. Maybe. When it shows up Monday at 10pm, it doesn’t work. Your lead actor’s visa wasn’t approved and she’s still in London. The suits show up to a late rehearsal or a shoot and demand a change. The studio has paid for product placement, and now you must work SmartWater into three scenes.

Subtle.

This? This is the tip of the iceberg. It’s a magical day when everything goes according to plan and no changes need to be made.

The idea behind “artistic freedom” is one of the best ideas ever: Artists should be able to engage with the world around them without constraints such as censorship. Artists with artistic freedom create better, usually more impactful and important, art under those conditions. But those conditions always exist within a given framework. Some constraints are practical (time, space, and budget), some are legal (the law, your contracts), some are ethical (best practices), some are artistic (imposed on the artists by the director or producer, or just by the basic parameters of the project), and some are social (updating outdated topical humor, avoiding lines, characters, or narrative tropes that would be considered racist, etc). Although not every artist recognizes or follows every constraint every time– sexual harassment is a huge problem in all these industries– artists as a whole work within these constraints without questioning them.

The social constraints we work within are never questioned, and usually framed in terms of audience response– a joke your audience won’t find funny, public controversy that could impact sales, or a scene that evokes a hostile audience response, which is entirely dependent on your social context. I’ve staged plays in Berkeley without an iota of controversy that later were picketed elsewhere in the country. Conversely, I’ve been sent plays whose entire plots centered around the Horrible! Revelation! that Someone! Had a Same Sex Affair! In College! My Berkeley audience would laugh out loud at the idea that anyone cared about your same sex college fling; such a play is unstageable here no matter how well-written because the premise is nonsense within our particular social context.

Land that I love. (Source: berkeley.edu)

So when we talk about the need for increased diversity (or the need to examine how various types of people are portrayed) in the theatre, film, and games we make, why is that seen as a massive, impossible imposition on an artist? We’re already working within a number of constraints and considerations, and, frankly, removing race as a primary consideration, instead using just type, talent, and skill set, doesn’t seem much of a constraint at all to me. All it takes is stating in calls (or instructing your casting people) that you’re open to actors of all races and ethnicities, and suddenly your hiring pool is expanded, not constrained.

That said, if you believe your work demands an all-white cast, no one is restricting– or can restrict– your right to use an all-white cast. No one can stop you from casting every lead with a white actor for the entirety of your career. So what, exactly, upsets people so much about calls for more diversity? Why is there so much angry backlash to discussing diversity in art? What people are upset about is that now consumers and critics are complaining about it. They don’t just want the freedom to use all-white casts, crew, and/or writing staff–they already have that. They want the freedom to do so without criticism.

This, by the way, is what they mean by “taking America back”– back to the days when shutting out people of color was completely uncontroversial.

Due to this desire to create all-white art without criticism, there has been an immense backlash, especially from the alt-right, about the very concept of using social criteria like diversity or the portrayal of women to evaluate art. They claim that this is a new development brought on by “political correctness” run amok, and that in the golden past, before feminism or Black people with twitter accounts, art was solely evaluated as art, and critical discussions of its social messaging were nowhere to be found.

This is, of course, bunk.

For centuries, art has been evaluated, formally and informally, using social messaging as part of the critique. In 472 BCE, Aeschylus was publicly criticized by Aristotle, who claimed Aeschylus’ play The Persians, about the Persian defeat at the hands of the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE, was too sympathetic to the Persians. Playwrights in Renaissance England went to great lengths to hide their critiques of the church or the government in metaphors that would get past the censors. When Paul Robeson played Othello in 1930, reviewers criticized the choice to cast a Black man instead of a white actor in blackface. One wrote: “There is no more reason to choose a negro to play Othello than to requisition a fat man for Falstaff.” There are literally thousands of similar examples from the past.

Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona and Paul Robeson as Othello in the 1930 Savoy Theatre production.

There are, of course, nearly as many examples from the present as well. While the right (alt and otherwise) bitterly condemns using diversity and other social justice-based criteria in evaluations of art, they themselves do this all the time. The right’s response to Beyoncé’s 2016 Super Bowl performance is an excellent example. Her performance came under fire solely for its pro-Black social messaging, which many on the right took to be “anti-white” and, somehow, “anti-police.” Ads for Old Navy and Cheerios featuring interracial families came under fire from right-wing racists for their social messaging alone. Evidently “interracial families eat breakfast and enjoy Old Navy 30% off sales” was a bridge too far for them. In 2012, the wildly popular, highly rated video game Mass Effect 3 included same sex relationship options (as they had throughout the series), but really came under fire for including a bedroom scene that many homophobic players complained bitterly about. (Of course, those of us who played through the game knew you had to click through many conversations with that gay character, continually taking the obviously marked “romance” option, to trigger that scene, or go out of your way to seek it out on youtube. But that’s none of my business.)

Steve Cortez from Mass Effect 3, who lost his husband to a Collector attack.

While some people do not wish to be told that people would like to see more diversity, they clearly have no problem telling us that diversity is, in essence, wrong.

There’s only one conclusion to draw here, and it’s not about “artistic freedom.”

For those of us who work in representational media, and must work within constraints both out of our control, like physics and budget, and well within our control, like personal artistic goals and vision, “artistic freedom” can be a touchy subject. We want as much artistic freedom as we can get, in part because we know that in reality, our freedom is constrained in multiple ways. Those of us calling for increased diversity (and equity) in film, theatre, TV, and games are simply asking our fellow content creators to consider diversity an important artistic criteria that exists alongside all the other self-imposed artistic criteria we all have.

Making a commitment to diversity is actually reducing your constraints, because it widens your hiring pool. Once you make the decision that a role can be cast with an actor of any race, or a show can be directed by a person of any race or gender, suddenly your hiring pool becomes much wider. Making a personal commitment to diversity increases your artistic freedom because it gives you far more to work with.

There is no true “artistic freedom,” including the many constraints artists put on themselves as they strive to meet (or exceed) their artistic goals. Encouraging others to make personal commitments to diversity– and holding them accountable when they do not– increases the artistic freedom both of the individual artists who would be widening their hiring pool considerably, and the artistic freedom of the industries as a whole, that would have a wider variety of artists working within it, which we all know is a massive strength.

So don’t believe anyone who tells you that calls for increased diversity or using diversity as a criteria for evaluation is limiting “artistic freedom.” We know better.