I invited actor and playwright Cameron McNary to write a guest blog about being a theatremaker who’s on the Autism Spectrum. I wish I had read this piece 20 years ago. Every theatremaker should read this piece! I learned so much I wish I could apply retroactively to my work.

ACTING WITH AUTISM

I can remember the moment I realized that Henry Higgins (the Pygmalion one, not so much the My Fair Lady One) was on the Autism Spectrum.

I don’t mean the kinda-sorta, nonspecific “Autismishness” that, say, Sheldon Cooper got because The Big Bang Theory‘s writers didn’t want to be pinned down by a real-world diagnosis that would force them to do the hard work of writing a neurodiverse character accurately. No, I mean, real, honest-to-goodness, straight from the DSM, if-this-diagnosis-existed-back-then-he-100-percent-woulda-had-it Autism Spectrum Disorder.

It wasn’t his obliviousness, his social awkwardness, his general dickishness. Sheldon Cooper has those, in spades. The clumsiness and lack of intrinsic concern for personal hygiene, well, that’s just a type: “The Geek.” Just Shaw’s considered observation of a “Man of Science.” Then I hit this line, in the middle of the philosophical and emotional blowout with Eliza that takes up the last chunk of Act V:

HIGGINS: The question is not whether I treat you rudely, but whether you ever heard me treat anyone else better.

Well, now. There, I’m starting to feel more than a little seen.

The passionate, blinkered application of a general rule to human social interaction? The kind that sounds really virtuous in theory but ultimately misses the point, vis-a-vis other human beings having feelings? A way of trying to bend the world around you so you don’t have to constantly burn so much energy considering the existence of other people?

Oh, yeah. I knew this guy. I knew him very well indeed.

Shaw, stage directions, top of Act II: “His manner varies from genial bullying when he is in a good humor to stormy petulance when anything goes wrong; but he is so entirely frank and void of malice that he remains likeable even in his least reasonable moments.”

That’s a precise description of how I survived grad school: I was mind-blowingly inconsiderate and generally insufferable, but I meant well– I mean so, so well– that ultimately you couldn’t hold it against me.

It was a profoundly comforting feeling to find out that people whose brains worked like mine existed in 1912.

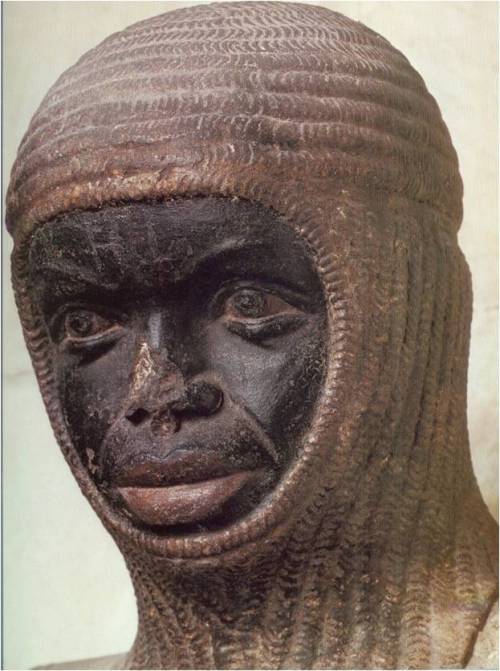

Again, I’m talking about this version of Higgins (Leslie Howard in a still from the film Pygmalion, 1938). My Fair Lady is wonderful, but it strips out about half of the ASD-like behaviors, and almost all of the context for them, and winds up with less of a sharply drawn portrait of a particular brand of humanity and more just Rex Harrison being charming and weird.

Shaw’s conception of Higgins had to come from somewhere– it was way too accurate in the particulars, and hung together too well as a whole, for it to be an invention from whole cloth. This is somebody– probably more than one– that Shaw knew. They existed. And they were like me. A lot like me.

It made playing him a real privilege.

So how does someone who has a developmental condition that involves “persistent challenges in social interaction, speech and nonverbal communication” wind up working as a professional actor and playwright? It’s more common than you might think.

(Disclaimer: My story is my own; “if you’ve met one person with ASD, you’ve met one person with ASD”; one size definitely does not fit all, etc.)

The theatre can be a surprisingly welcoming place to someone with ASD. For all its air of loosey-goosey do-what-thou-wilt bohemian home-for-freakery, to someone who looks at social rules explicitly, as puzzles to be figured out, the unspoken laws of the theatre are both easy to articulate and satisfyingly unbending. “Five” means “five.” Be 15 minutes early. Never give another actor notes. Say “thank you” every time it’s humanly possible. Have we worked together before? Broad smiles and that friendly back-pat hug at the first reading, even if we don’t like each other. Especially if we don’t like each other.

Acting company etiquette evolved literally over centuries to allow multiple powerful, attention-hungry (and sometimes fragile) egos to work together efficiently. It gives broad latitude to attention-seeking behavior that doesn’t get in the way of the work, and clamps down hard on any that does.

A lot of ASD-fueled behavior can look like attention-seeking. Which means when you slot into a group of loud, emotionally sensitive theatre kids, you don’t really look all that out of place. And when you’ve also got a powerful, attention-hungry (and sometimes fragile) ego to go along with that ASD, well, it’s very easy for the theatre to start to feel like home.

Where I’ve often run into trouble is with my sometimes inflexible way of thinking. “Just take the note” is one rule that’s taken me a long time to internalize. My artistic choices can often set very quickly, and can have a “stuck on a track” quality. We’ve all seen actors argue with a note, passionately convinced that the scene in their head is the only way it can be. I do that too, but trust me when I say this is different. When a director pops my already-conceived notion of the way the scene just has to go, it takes me a lot longer to recover than other people to put the pieces back together. There’s no malice to it, and it’s actually not an issue of ego– although it can certainly look like one. My mind loves rulesets, and is only comfortable when those rulesets are well-defined and strongly in place. If a director smacks up against one of those rulesets, I can’t just change the line reading or the blocking or whatever. I have to build a new ruleset that can contain this new bit of information. And that can take a moment.

“You need to know: although I know it looks like it, the expression on my face does not mean I think your note is stupid and you’re an idiot who can’t direct. It’s just the way my face looks when I’m recalibrating.” ← Words I have actually said to a director in a professional production.

There’s also the fact that, like Henry Higgins, I am by nature incredibly inconsiderate. It doesn’t mean I don’t like you, or you’re not important to me; it means you’ve got a chip in you somewhere that’s constantly considering other people’s needs, and I don’t. I’ve had to develop habits that do the same thing instead. After four and some-odd decades’ worth of practice, those habits are very, very good at their job. But they’re not infallible. I’ll always be processing information about the needs of those around me on equipment that just wasn’t designed for it.

The best way to accommodate that is one I try to give people a heads-up about whenever possible: hold me to account for the things you need from me, emotionally or otherwise, but know the best way to get me to actually do those things is to explicitly tell me what you need. I do really, really well with things that are explicit.

We tend to think of theatre, and especially acting, as being primarily about emotional truth. And I guess it is, for most actors I’ve met. I mean, I get there eventually, if I’m doing my job, but that’s almost never where I start. I start with the gestures that play, the line readings that sing, and most importantly, knowing what my job is: knowing what I need to be doing at every moment to serve the story. What needs to happen, and what do I need to do to make it happen? Not my character, mind you: me as a performer.

I have been told I think about acting like a director. Some of the people who have said this even meant it as a compliment.

I come at acting– I have always come at acting– from a fundamentally different direction than most of the other actors I’ve met. They start with what their character wants and needs; who their character is. I usually start with poses, and making faces, and line readings. Also a funny voice if I can at all help it.

I am not even kidding. Somehow it usually works, too.

I’m used to people rolling their eyes at the acting styles of yesteryear: your Booths and Barrymores and Bernhardts, clutching their forelocks and biting their fingers and oh sweet lord Larry Olivier doing that dying swan ballet thing when he dies as Richard III . . . and all I can think is: oh god, what I wouldn’t give to get away with that shit.

Different actors have different strengths and weaknesses, of course. Making it truly authentic can be hard for me. I have yet to really find my groove on film. I sometimes have difficulty with scenes more intuitive actors can take to like water. On the other hand, I have no problem doing some otherwise unmotivated theatrical shit for Brecht. I’m never disappointed when speaking Shakespeare clearly gets in the way of my emoting. And you never, ever, ever have to tell me to find my light. Get in between me and my light and I will mow you down. I will feel bad about it afterwards, but then I’ll realize it was my light, and I won’t.

I think non-ASD actors and I were born with the same theatrical sense: what I think people are talking about when they use the word “talent” in relation to acting in the theatre. We’re all able to sense what an audience wants, and more importantly what they need, and fulfilling it is a goddamn drug to all of us. But neurotypical folks see the emotional through the lens of . . . well, the emotional. They don’t have to think about it at all, really. They just read emotions like a fish reads water pressure. I have to work at it. I’m not like, emotion-blind or anything, but it’s like all those emotions are on the ceiling, and to read them I have to tilt my neck back and look up. It’s not a huge deal, and I do it out of habit pretty easily by now, but it is a conscious, explicit action, and it always takes effort. So my instinct has always been to come at what that audience needs at a right angle from most actors.

Eye contact, for instance: ever wonder why someone with ASD avoids eye contact? It’s not because it’s bad or scary (at least for me). But it’s always significant, and drains at least a small amount of my emotional energy while I’m doing it.

I mean, I can look you in the eye if the scene needs it, if you need it from me as a scene partner, but if we could be blocked gazing out over the audience into the middle distance? If that’s a possibility? Oh, I’m at least gonna try that.

(Also, people in real life don’t make eye contact as much as you think they do. Definitely not as much as actors do on stage.)

Again, how could somebody who can’t perceive emotions know such a thing?

Again, I can perceive emotions just fine. They’re just up there on the ceiling and ugh . . . effort.

But it’s an effort I’ve had to make a lot as a social animal. In my time on this Earth, I may not have liked studying how my fellow humans behave, but I have done it a lot, because I had to. Neurotypical people get so annoyed when someone doesn’t know how they work.

Writers like Stoppard and Nabokov– non-native English speakers– bring something to writing English that native speakers never could. There’s something about coming at a mother tongue at an angle that lets you see things– connections, turns of phrase, linguistic opportunities– that just can’t be seen from straight on.

So it is with actors. Actors with ASD come at human behavior at least a little widdershins. Yeah, it can be a pain in the ass for all involved, but it can also let us see things about emotional truth and the performance thereof that neurotypicals just can’t coming at it the easy way ‘round.

When Sir Anthony Hopkins was asked in a 2017 interview with the Daily Mail if his ASD had affected his acting, he said, “I definitely look at people differently . . . I get offered a lot of controlling parts. . . . And maybe I am very controlled because I’ve had to be. I don’t question it, I just take the parts because I’m an actor and that’s what I do.”

Which is something we have in common with neurotypical actors, I think: we don’t question it too much, and we take the parts.

But sometimes it’s helpful to know the hows and whys of our own behavior, and of the folks we get to work with. Sometimes I’m very thankful to Shaw, and the mirror he was holding up to nature in Henry Higgins. Definitely for that delicious, delicious role, but also for letting me feel a little more seen, over a century away.

Cameron McNary is an actor and playwright living in the Baltimore/DC area. His plays include OF DICE AND MEN, SHOGGOTHS ON THE VELDT, and BED AND BREAKFAST OF THE DAMNED.

Support Bitter Gertrude by becoming a Patreon patron!