I looked for ages for a photo credit for this. If anyone knows this super-adorable kid, or the photographer, drop me a line. I found it on beautyofhijabs.tumblr.com.

Theatre has a certain . . . reputation, no? That professional theatremakers are an iconoclastic, irreverent community that ignores or even outright disrespects religion?

The reality is, as reality always tends to be, much more complex. It’s not uncommon, however, for religion to be invisible, or even denigrated, in some professional theatre circles.

People who grow up in Christian heritage families (and note that that isn’t the same as being Christian or practicing Christianity) have massive privilege in this country. Privilege creates a certain world view that, when left unexamined, deeply marginalizes people outside that privilege. Christian heritage privilege functions no differently than any other kind of privilege. It’s not that people with Christian heritage privilege overtly believe that Christianity is superior to all other faiths. Obviously, some do, but that’s not what I’m discussing here. What I’m talking about is unconscious bias.

Most people with Christian heritage privilege who have not examined that privilege have an unconscious bias that all religion functions like American Christianity (privilege believes “my experience = reality”); that all religion shares certain basic characteristics, beliefs, or principles with American Christianity (privilege believes “my understanding = truth”), and that Christianity is the dominant religion in the world (while Christians make up 70% of the US, they’re just 32% of the world).

Even people who have no real contact with religion apart from what they glean from popular culture, but who have unexamined Christian heritage privilege or have internalized its world view just from living in this culture often have this bias. Conservative Christianity is the most highly publicized religion in the nation. Every other type of Christianity is so completely overshadowed in popular culture as to be rendered invisible or tainted by association. Every other religion is either ignored or represented in wildly inaccurate or reductivist ways that are deeply colored by the world view of Christian heritage privilege. Conservative Christianity, the public face of religion in America, is taken by those with unexamined Christian heritage privilege and those who have internalized that world view as the basic definition of “religion.”

A certain kind of morality (anti-LGBT, anti-feminist, “pro-life”), certain political stances (anti-public assistance, pro-death penalty, anti-separation clause), certain practices (evangelizing, praying as wish fulfillment, tithing), and certain religious beliefs (male god in the sky, eternal hell for nonbelievers, original sin) are taken together as all the defining factors of “religion” rather than a certain type of Christianity.

This is a great example. Not all religions are exclusive like conservative Christianity. Not even all the religions depicted on this meme are exclusive.

Therefore, it’s no surprise that some people who don’t come from observant families and aren’t observant themselves– an enormous, ever-increasing percentage of Americans– conflate this public, conservative Christianity with “religion” and conclude that “religion” is bad, whether they personally believe in a god (or gods) or not. And while most “nones,” (people who claim no religious affiliation) including atheists, are accepting of difference, a small but unfortunately vocal subset are actively hostile to all religion.

While there are certainly people who have come to an intolerantly anti-religion stance from non-Christian families, assuming all religions are like the ones they (or their forebears) left, the vast majority of anti-religious people in America, like the vast majority of people in America in general, come from Christian heritage privilege. Anyone who grew up in this country grew up surrounded by the erroneous concept that Christianity = “religion,” and that all religions function like Christianity in most ways. Some examine that world view and discover that it’s inaccurate, while others never examine it, some even expressing extreme fragility around the idea that Christian heritage privilege and its attendant world view exist at all. I’ve heard any number of people talk about all the “studying” they’ve done about “world religions,” yet claiming they’re “all alike,” a sure sign that their “studying” amounted to a Buzzfeed article on The Craft and half a documentary on Netflix about Orthodox Jews before they got bored and fired up Bloodborne.

Open hostility to religion and religious people is one of the few acceptable public bigotries left to liberals, so people will go to great lengths to protect it by crafting all sorts of justifications, asserting that religious people are all hateful of nonbelievers, “stupid,” “delusional,” and responsible for the majority of society’s ills, bolstered by unexamined Christian heritage privilege bias that unquestioningly sees “religion” as identical in form and function to conservative Christianity. This point of view highlights where that’s the case (as in fundamentalist Islam’s anti-LGBT stance) and minimizes or ignores where it’s not, rather than accepts that “religion” is a category so diverse that there’s not a single thing that could be said to define it across the board, not even a belief in a god or gods.

The impact in the theatre community is clear when you begin to look for it. More professional theatremakers than you think are religiously observant, and it’s no surprise that many hide that fact because they worry about their colleagues’ potential reactions.

I’ve been thinking about these issues for awhile. When you start to look for something, you see it everywhere, and it became clear to me that there is a large, but largely invisible, segment of our community that is religiously observant and, in many cases, hiding it, or hiding its full extent, anxious about their colleagues’ reactions. And while I’m not advocating for pushing this issue to the forefront past other issues of privilege and inclusion like race and gender, I am advocating for deeper thought around this issue, more kindness, and more acceptance, from everyone, on all sides, religious, atheist, and everyone in between.

A number of religiously observant theatre professionals volunteered to be part of this blog post. I wanted to give these people a voice, but allow them to retain their anonymity if they so chose, so some of the names below are real, and some are pseudonyms, but they are all real answers from real people. So here you go, theatre community. The religiously observant people with whom you’re already working, in their own words, discussing theatre and their faiths.

A Wiccan wedding, called a “handfasting.” Photo cred: leavemetomyprojects.com

What are the largest challenges you face as a religiously observant theatre professional?

Rowan, Wiccan director, Chicago:

Scheduling around events. Sometimes there are just unavoidable conflicts, and most of the time, I let my career come first. Discrimination against Wiccans is common, so most of us are in the broom closet, as we say. You can’t be open unless you know you’re in a safe space.

Larissa, Christian playwright, Santa Monica:

Scheduling during Christmas and Easter. I have performed shows on both holidays, but when it is a matter of rehearsal I let them know up front that I am one of two altos in our choir so if it is possible to give me an hour on Sundays to come in later if everyone isn’t always called, I would appreciate it. Sometime people are cool with it, often not, which is fine. I made the choice to accept the job so I don’t press it. However it is hard to hear the snide remarks about my being a Christian and missing church, which I never mention in the work place unless asked directly.

Nick, Quaker actor, San Francisco Bay Area:

I used to be really challenged whenever taking on roles. My concern was not so much about whether or not I am going to do something bad or sinful in a performance, but whether or not the piece of art as a whole that I am helping to create is creating goodness and beauty in the world. I am less concerned about that now, because my values have changed and I have more faith in the goodness of people than I used to. I was never super fundamentalist and felt like if it wasn’t a Christian message then it is evil, but I leaned more in that direction. However, this does still matter to me. I feel like my job as an artist is to create goodness and beauty in the world, to create the new heaven and new earth. For that reason I try to join artists who are doing that. The most important role I’ve been in was 8, a staged reading of the overturning of Proposition 8.

Linda, Buddhist stage manager, San Francisco Bay Area:

SCHEDULING. The best and the worst thing about being a Buddhist juggling production schedules is one and the same: how I practice is flexible. (The biggest challenge is not specific to theatre: the general public is very confused about Buddhism.) When a schedule conflict unexpectedly arises, I am more likely than not automatically expected to forego my commitment to my practice just because I can and just because ultimately I “only” answer to myself. Most productions have been good about keeping to a previously agreed upon schedule and being accommodating when schedules change. (Most, but not all.)

Andy, Christian playwright, Rhode Island:

I would probably say my biggest challenge is translating what are essentially religious themes into a modern idiom that is accessible to people from diverse backgrounds. This doesn’t mean watering down the religious content of my plays, but it does mean grounding them in real human emotions. What religion essentially is to me is a deep affirmation of the dignity and worthiness of each human, and as such is provides a very useful frame to examine long-standing conflicts of the human condition.

Alona, Jewish actor and director, New York:

I am a modern orthodox Jew. Every Friday night at sundown, until three stars appear on Saturday, I go into full-out Sabbath-mode: no using electricity, no driving or using public transportation, no cooking, no listening to or making music, no money, no writing, no carrying items outside of buildings. The list goes on and on, and it doesn’t mix with the world of professional theatre.

By acting in professional theatre, you are agreeing to a life of of Saturdays spent using microphones, being lit by stage lights, getting paid for working. You are also probably agreeing to work in theatres that are not a walkable distance from your home, and even if they are, you are agreeing to come to rehearsals prepared, which often means carrying your script (and food and a water bottle) outside. Usually you are expected to be ready to write down blocking or line changes, to be reachable by phone or email for last-minute schedule changes, and to listen to whatever music is included in the show or rehearsal or workshops. And while some theaters don’t perform on Sunday, I can name only one theater that never has Friday night/Saturday shows or rehearsals (shoutout to 24/6 in NYC). All of these things become extremely problematic very quickly.

In sixth grade, I moved to New Jersey and auditioned for Paper Mill Playhouse’s summer conservatory. At the time, my family and I were incredibly naive about all things theatre: my father answered the call and gave the casting director a grateful thanks-but-no-thanks. I wouldn’t be able to go to rehearsals or do shows on the Sabbath, he explained, and besides, opening night would be on Shavuot, a Jewish holiday. The casting director thanked my father and hung up. I was devastated. Fortunately, she called back, promising to work around any conflicts with Judaism. Looking back, I see how incredibly rare and accommodating that second phone call was; it’s a gesture I’m not going to forget. Paper Mill was wonderful about everything. They set up the double casting schedule so I’d have as few Sabbath performances as possible. That press opening coinciding with Shavuot was an unavoidable conflict, but they let me and my mother stay in an apartment just across the street from the theatre so I could walk over, and continued to let me do so for every Shabbat throughout the run.

I thought I’d solved the dilemma. But I was wrong. As I did more and more theatere, the conflict got harder and harder to deal with. Each show presented a new set of obstacles, a new set of decisions to navigate and compromises to make. Because where do you draw the line? If you’re signed on to a show and suddenly you have to eat onstage, do you ask the stage manager to buy (often more expensive) kosher food? What if painting or writing is written into a part? I can decide to listen to the orchestra playing, but what happens I’m asked to accompany myself with an instrument onstage? It’s a very tenuous balance to strike — and potentially destructive, too, because making too many compromises on either side has the potential to alienate you from either community. Taking on a high-profile role at a local theater could mean publicizing the fact that you’re breaking Shabbat, which could mean that some people in the Jewish community might stop trusting your standards of keeping kosher, and no longer feel comfortable eating at your house. Conversely, it’s easy to be “too difficult to work with” in the theater: being associated with a set of mysterious rules and conflicts could raise red flags for companies who don’t know what to expect. So there’s a balance between being up-front about potential conflicts and not scaring off theatre companies. If I anticipate any big problems or conflicts I’ll note it on the audition form — holidays like Rosh Hashana or Passover, for example. Sometimes I’ll even write something like: “talk to me about the Sabbath — some restrictions but shouldn’t be a big issue.” Being reassuring is important – people who are dealing with this situation for the first time might think it will be impossible. Part of my side of the bargain is letting them know that I’ve successfully struck a workable balance in the past, and that this can work out this time too. In fact, it will hopefully (probably?) be barely noticeable to them.

Jerry, Christian playwright and actor, San Francisco Bay Area:

I feel that I have been fortunate that my theater practice and Christianity have not been much in conflict, except the occasional timing issue between church letting out on Sunday morning and a tech rehearsal or performance. Belonging to a Lutheran church, there has been no onus about working in the theatre, and as a devout Christian, my writing is primarily focused on good and evil with good being an active verb rather than a responsive partner. Does that make sense? Based in my Christian faith, I believe that good is something one does, not merely something one is. As an actor, I have never been asked to do a part that was in conflict with my faith. Of course, I am not so sure it is the same for more dedicated actors. There are more of them than roles, and desperation can be a mighty powerful influence. I suppose it all comes down to values, and are we as artists true to them, whether they are faith-based or general personal ethics. I know what my values are, what kind of work I want to be a part of and what kind I don’t. For example, I don’t think I could be involved in a theater production of any kind where evil acts or evil people are glorified. Even for good money.

Ariel, Muslim actor, San Francisco Bay Area:

I think as a woman who wears the hijab, and a convert who is also a theatre professional, the biggest challenge so far has been more internal, figuring out what MY line is. For me having graduated college and immediately jumping into work in the city while at the exact same time jumping in and embracing my newfound faith has really had my brain cooking as to where do I set the line. We as women are so hypersexualized that it is constantly in the back of my head. I ask myself questions like, Should I wear my hijab when I audition? Will they feel weird? Should I tell them no, I don’t feel comfortable doing this? Will that hurt my chances? How will my castmates react to me? Was taking my hijab off in the audition room a good idea or not? If I show my hair will that give me a better chance? The questions sound silly, even to me, but as a woman in theatre who used to think “I’m always going to be sexualized in this game, so why turn down roles just because I feel uncomfortable,” these questions are real.

Photographer: Kris Krüg

Have you ever had to compromise either your faith or your art due to your commitment to living as a religiously observant theatremaker?

Rowan:

I turned down a show because it had a stereotypical caricature of a Wiccan in it, just there for laughs. Just mockery. And I couldn’t say why. I faked a response about scheduling. I would have loved to do the show. I don’t know what their relationship with the playwright was. I didn’t feel like I could ask for changes to the script. I’d rather not stick my neck out about it and get labeled a problem or deal with bigotry.

Larissa:

I keep my mouth closed a lot when people are Christian bashing at work because I don’t want to become a target. I am often amazed that the same theatre people who are intolerant of hate speech toward Muslims or Jews will openly tear apart ALL Christians during work and think nothing of it. That kind of hate speech is completely tolerated at our theatre work places.

Nick:

When I was less progressive, I used to believe that homosexuality was a sin. The first show I did with [company] was Merchant of Venice, and Antonio was directed to be openly gay. Even though I believed homosexuality in particular was a sin, that was such a small piece of the beautiful piece of work the director created. His Merchant was above forgiveness and terrifying consequences of rumors and prejudice. It didn’t matter what my beliefs about homosexuality were. It doesn’t matter that I may disagree with this director on one particular, because overall I know that he is making the world better. If there are scheduling conflicts between rehearsals and religious meetings or holidays, I will let rehearsal win. I view my art as a religious practice, so there is no compromise for me in creating art instead of going to church.

Linda:

I rarely compromise in theatre, which means I do often compromise going to temple. Working in theatre also involves late nights, which makes getting to temple early the next day more a chore than the joyful chance to recharge it usually is. What this usually means is I compromise on recreation and keeping up with pop culture.

Andy:

I will refuse to do any theatre that conflicts with my religious beliefs, but in a very general sense. That is, I will refuse to do plays that do not affirm the basic dignity of human beings. This doesn’t feel like a compromise to me.

Alona:

The hardest thing for me was the realization that it was impossible to practice modern Orthodox Judaism and also do professional theatre. I would have to compromise one or both, and I think that’s the saddest thing. But in the world of inevitable-compromise-making, I have been incredibly lucky to work with amazingly understanding people: directors and SMs and castmates and techs who will go out of their way to print their notes instead of emailing them, to coordinate schedules so that I’m not called on Shabbat, to make sure I’m not walking home alone without a phone at night, to sign my name on the callboard.

But there are still trade-offs. The biggest compromise I’ve ever had: a role I’d been dreaming of playing for ages, a fantastic director, a great cast. There was just one problem — one of the performances was on Yom Kippur. By that point I’d come to terms with performing on Shabbat, but Yom Kippur, the Holiest of Holy Days — that was on another level entirely. So when I got the call that I’d been cast, the classic rush of excitement was tainted by apprehension. I tentatively brought up the subject of Yom Kippur: was there any conceivable way to work around my conflict for that single date? The answer was (understandably) no.

Reconciling Judaism and theater had always happened on fluid spectrum; the decisions I’d had to make were always how-much-how-little, never either-or. Suddenly they were pitted against each other. I imagined, for the first time in my life, not observing Yom Kippur: not being in synagogue to hear the shofar blow, not fasting, not being with my family. I also imagined the pang of regret I’d feel every time I looked back at the road not traveled, the role never played. I talked myself out of taking the part, and I talked myself back in. In the end, I took the role.

The show ended up being a lot of fun, and I don’t regret signing on. But I do regret performing the night of Yom Kippur. First of all, though I was there in body, as I’d agreed to be when I’d signed the contract, I wasn’t there in mind. Ironically, though, my performance wasn’t the only thing that was a disaster that night. At two minutes to curtain, paramedics rushed into the theatre to take an elderly audience member to the hospital (she ended up being fine). During the show, lights broke, props broke, cues were missed, lines were dropped. Disaster upon disaster. It was, objectively, the worst performance of the run. And all through the performance that night, I thought about the story of Jonah and the whale, which we read in the synagogue every Yom Kippur. In part of the story, Jonah tries to flee God by boarding a ship. God sees through Jonah’s plan and creates a storm to destroy the ship: the ship’s crew panics, and Jonah, realizing that the storm is his own fault, his own punishment, tells them to toss him into the sea. So they do, the storm stops, and they are saved. I’m not usually particularly spiritual or superstitious, and my agnosticism remained (and continues to remain) sound, but that night, as the show (sometimes literally) crumbled around me, the irony of the situation was overwhelming. I wanted to shout to my fellow actors: “It’s my fault! Toss me off the stage and you’ll be saved!” Now I know: no more performing on Yom Kippur for me.

Jerry:

Pardon me for being a bit obnoxious about this one, but life is full of compromises. Still, I have never given up my core faith or artistic bearing for the other. I have never been in the position where I actually had to turn down or refuse anything because of my faith, or take part in something that was contrary to my faith. Doing good is who I try to be. Writing/theatre is my vocation. Being Christian is who I am. At least for me, all of these are interconnected. I sometimes have remarked in serious jest that as a writer/theatre artist, I have a higher calling than a minister has. (My pastor doesn’t like when I say that.) Where the pastoral calling is generally (but not always) for a specific congregation, an artist’s calling is to spread goodness, and even the good news of God’s grace (in a variety of ways, some of them very subtle) to the world.

Ariel:

I have been very fortunate to not have come across a scenario where I had to compromise my art or faith. Despite my own internal anxieties, the Bay Area theatre community in which I have been blessed to work has been really awesome in not putting me in a situation where I feel uncomfortable. I’ve also done my homework to avoid anything that won’t mesh well. I’m honestly figuring it all out along with everyone else, what I do or do not want to do. I will say this, though– when prayer time is the same as performance it does get a little tricky.

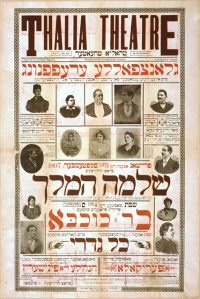

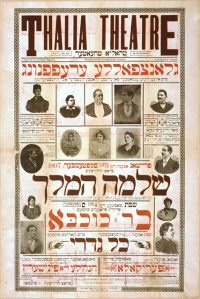

A Yiddish theatre poster, New York, 1891.

Has your faith impacted your approach to your art?

Rowan:

We get to truths through storytelling that we can’t get to any other way. Theatre is magic, I believe that. I think people who see it as entertainment or just a job are missing out. Wicca impacts the way I see the world. I feel like the social justice focus I bring to my work is a big part of my faith. Even when the play isn’t specifically about a social justice issue, who you cast and how you treat them are.

Larissa:

I believe in a God that has a plan for my life, so I am able to be fearless and walk though doors that many theatre people cannot because of the lack of a safety net, but I always have one, God. I love that I have a place I can go to every week to remember that there are bigger issues in the world than a light cue or line rewrite. I get to go to church and think about things that are bigger than my life and share that peace with people who have nothing to do with my job. I love that time to unplug and refocus. I don’t know how non-religious people do it. I pray for God’s will in my life and walk forward with every path that is put in front of me, knowing that He will make it work out. I’m also very aware of needing my art to do something positive in the world. I don’t convert people through my art, but I need it to make a real life difference to people. To change things. I think that’s part of what draws people to my work, the desire to do something more than entertain.

Nick:

I am really biblically literate and I also do a lot of Shakespeare. It’s always fun knowing all of the Biblical references that he makes. “O Jephtha, judge of Israel, what a treasure hadst thou!” Fucking Jephtha. Each Quaker meeting (“church”) has a book called “Faith and Practice” which outlines what they try to believe and how they try to live. Being a Quaker is so much about living and practicing your faith. Like I said before, I try to create beauty in the world, so my work in the theatre (and all the work) that I do, I see as a religious practice. Even though I am a Quaker, I was raised Catholic and still love the liturgical language of the Catholic and mainline churches. I often think of theatre artists working together as communion.

Linda:

Spirituality and art are integral parts of a benevolent cycle. By cultivating compassion, sympathy, and empathy I “hear” the resonance better and that can only make me a better storyteller.

Alona:

I’ve always thought of people’s warm-ups and pre-show rituals as a kind of religion. There’s lots of tradition and spirituality in doing a sequence of stretches and repeating certain phrases – and also in holding hands in a circle before opening night, in what you’re not allowed to say backstage, and how to respond to stage managers (at the risk of sounding irreverent – I mean it very reverently, in fact – is a “thank you, five” really so different from an “amen”?). And also both theatre and religion tend to be simultaneously very communal and very internal – they both rely very much on participating with a group, be it a cast or congregation, while at the same time eliciting (and sometimes requiring) a parallel inner experience.

I also have a lot of plays in my head about Judaism and Jewish identity that have yet to be written, and I’d love to start getting them on paper to see what sort of dialogue comes out of them in rehearsal rooms and in audiences. The few times I’ve gotten to be in spaces where theatre and Judaism overlap (watching shows like Body Awareness, for example, or parts of Fires in the Mirror, and yes, also Fiddler) have been really exciting for me: theatre is a medium that I feel very at home with, and Judaism is such a huge yet completely mysterious part of who I am, so it’s exciting to see theatre used to tackle some of the questions I still have about that whole side of life. Tradition, tradition.

Jerry:

As a Christian, I am a disciple, and part of being that disciple is to love my neighbor. Who is my neighbor? The great theologian Martin Luther defined the neighbor is anyone who needs what I have to give. So I get to give my storytelling, my love of stories, my love of my fellow human beings, my dedication to the marginalized, my love of the wonderfulness of life to the world—through making theatre. I get to truly be a Christian, and spread the good news that we are all valuable, beautiful human beings through live-action stories. I get to serve my sisters and brothers. Golly, I could go on and on.

I love the stories of my faith, and I love the parables of Jesus Christ. As an artist, I am dedicated to doing good in the world. In the theatre I get to do this by telling stories about how wonderful and beautiful human beings are.

Andy:

I have access to an incredibly rich store of images and stories that all deal with the most profound questions of human existence. Being religious puts me in contact with people I would otherwise rarely know. I have friends who are 80. I have friends who are homeless. I have friends who are special needs. These are people I probably would never have met if we weren’t united by our faith. But the history of Christianity is also a great inspiration. Being religious in the way I am forces me to understand our present moment in its historical context, which is still deeply Christian, so I think in a way being Christian helps me understand how we got where we are. It’s a great resource, my faith.

Ariel:

I’ve been able to meet people of other faiths who share their stories and it’s been really enlightening. The most important thing for me, especially at this time where Islam in particular is being portrayed in the media as evil, and Muslims are being associated with murder, terror, evil, and radicalism, is to be able to say, “no, that is not who we are,” and it’s nice to have met people who have said, “yeah, I know,” or are just willing to listen. To debunk even the smallest of things or explain why we believe this or that, especially as a woman where there are all these misconceptions about how we are treated in Islam. It’s been nice to be able to have discussions and answer questions.

My faith has impacted my art in that I have been able to be more aware of the human condition, being able to take a piece or a character and look at it more deeply. It’s inspired me to engage more in pieces that challenge government, examine the “roles” of women and men, embrace color, sexuality, all points of view. In a way my faith as made me pickier, more selective. Thinking less “me” and more “us.”

People gathered for a Quaker meeting. Photo cred: Philip Greenspun

Has your art impacted your approach to your faith?

Rowan:

I love props and costumes and I use them in ritual all the time. Wicca can be very theatrical. It doesn’t have to be, but being a director, I think I have a visual, spatial approach to ritual, and how its theatrical aspects can impact people.

Larissa:

I’m definitely very aware that I work with non-Christians most of the time, and that makes me super aware of the bubble a lot of Christian live in. They really have no clue how the rest of the world thinks. That ignorance grows into intolerance. I see it happening all the time and it makes me so frustrated with being a Christian. It’s embarrassing.

Nick:

I think that Hamlet’s words to Horatio at the end of Hamlet have probably become as central of a religious text in my life as the Bible. “Not a whit. We defy augury. There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, tis not to come, if it be not to come it will be now, if it be not now yet it will come. Since no man knows aught he leaves what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.” Hamlet is also referencing Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel, so it’s fitting that I dig that.

Working in the theatre has also further instilled in me that idea that we live our faith in the world in our daily lives. Sometimes when I go to meeting (church), I see a bunch of people singing songs, pretending they feel a certain way, and listening to a very intellectual heady sermon, pretending they believe certain things (defining belief not as your practice in life or even what’s in your heart but intellectual assent to ideas), and I think what the fuck is the point? Then I go to the theatre and I see a group of people working together, supporting one another, to create beauty in the world, and I think, “This is the Church.”

Linda:

Deepening the understanding of humanity in all its many facets enlightens my understanding of my own foibles and what I might be able to do about them. A lot of Buddhism revolves around not giving one’s own ego free rein and one way to do that is putting yourself in someone else’s shoe, which is a skill storytelling can hone.

Alona:

Aside from helping me recognize that tradition can be dynamic on a personal level (as opposed to just societal), I don’t think it has….Hm, I’ve never really thought about this before! Maybe it’s something I’m still figuring out. I do know that I ironically hate “performing” in religious contexts – on the rare occasions that I go to an all-women’s minyan, I try to stay away from reading from the megillah and things like that.

Jerry:

I think they are intertwined; one impacts the other. But I believe I think more deeply about my faith because I am a writer. I apply (and when I teach Christian education relate) a basic premise I use in theater to the stories of my faith: What is it about? Not just what happens, but what is the story about. I also think a lot about truths – from my art to my faith, which is a different way of saying what I just did. Is this a true story? Do I believe it? Not do I believe it is factual, but does it tell me something important about human nature, or in the case of Christianity, God’s relationship to us and our relationships to each other?

The Thai Buddhist temple in my hometown of Fremont, CA. More info at watbuddha.org.

What would you like the theatre community to know about your faith?

Rowan:

There are people out there who try to debunk Wicca by saying it’s less than 100 years old, which is both true and not true. The loosely organized theology of Wicca as an alternative faith has developed over the past 100 years, but the pagan traditions it’s based on are thousands of years old. My grandparents on my mom’s side came here from eastern Europe. They were Catholic. My grandmother taught us all kinds of things that she believed were Catholic traditions from the old country. House blessings, little rituals she said were for “good luck” or to ward off “bad luck.” But they weren’t Catholic at all. Hang this herb above the door, stuff like that. She claimed that this was our tradition as Catholics. I later read about the Christianizing of eastern Europe, and how Slavic peasants practiced their old religion and Christianity at the same time for centuries. Some of her traditions had to come from that. I wish people had more respect for Wicca. I’d love to be able to live more openly.

Larissa:

It’s the base of all the things you like about me. It’s why I’m such an optimistic person. It’s why I have real joy in my life. It’s why I take risks and fall and keep getting up. I approach every day with an intentional desire to show love and forgiveness to everyone, in the same way I believe Christ forgives everyone. We are all equal sinners in his eyes and all equally forgiven, so I don’t judge anyone. That intention is directly from my faith and, when I’m doing well at it, makes all of our days better.

Nick:

Not all Christians are homophobic. There is a huge growing number of Christians who believe that homosexuality is not sinful. I don’t want people to know that because the opinion of Christians matters at all. What Christians believe about people’s’ sex lives is completely irrelevant, and no one needs approval from Christians. I only say that because I want LGBTQ people to know that there are less people in the world that hate them and more and more who love and accept them. Also I kind of want people to know that I really really love to talk about religion and I have no interest at all in converting you, but I wouldn’t apply that as a rule to Christians. Don’t talk to them about religion. They totally want to convert you.

Linda:

Competing with other religion/faith/spirituality does not have to be part of all religions and in fact, it’s not part of Buddhism. This is inconceivable to most Americans. Buddhist services are not on the same day of the week every week. This is also inconceivable to most Americans. Gravity is not a bitch therefore neither is Karma.

Andy:

I would like the theatre community know that there is beauty, wisdom, and nuance in these traditions. Religious people are not crazy, we just have a different way of making sense of the world that secular people do. And I don’t think that’s because we ignore or denegrate anything about the secular world. I think it’s because we see the secular world as infinitely valuable because it is the creation of a loving God. This conception of the structure of the universe forms our mind in indelible ways, and asking us to translate these ideas into secular terms does them irrevocable violence. Theatre could do a better job understanding that, but then again we could do a better job explaining. They should all read Augustine’s Confessions and Teresa of Avila’s Life and then tell me what they think about Christians.

Alona:

There is no single set of rules for Judaism. Even just within Modern Orthodoxy, there are countless different traditions based on ancestry and family and what is available for you to practice where you currently live. And even within that, I’ve picked and chosen and molded what works for me – and even THEN, tradition itself isn’t static. So there’s no definitive set of rules I can point to and say “these are the rules I live by and this is exactly how they’ll affect this theatre-making process.” In practice I often have to decide ahead of time what rules I’ll keep and what I’ll let slide, since it can be confusing to change midway through, even if I see the change as being more accommodating by deciding that I’m okay with doing something I might normally feel iffy about. But most of the time the “…But last week you said you couldn’t do that!” and possible “Can you do this also then?” isn’t worth the confusion.

When I was a child doing theatre, most of the sacrifices were on my parent’s end. I just found an email my mother cc’d me on from years ago (sent to another mother asking about balancing Shabbat and theatre for her own child). The email said: “Your eyes would pop out if you knew some of the crazy things we have done to make things like this work. Worth it???? Overall, yes. And, it helps your kids see that it is okay to let people know (and how to talk about) what your boundaries and needs are – and most of the time a balance can be reached.” When I got older, they talked me through the tough decisions. They never said: “This is what you should do,” or even “This is what I would do” — not even when I begged them to give me an answer, any answer. There was no answer, they said, just finding out what I myself was comfortable with.

Jerry:

To me it is a great shame that so much of our media, which so many of us think is full of exaggeration and falsehoods in so many other areas, has become so “true” when it comes, in particular, to Christians. Golly, if I only thought of Christians as being those who pontificate about others’ “sins” and wrongnesses, or how God is full of hatred toward certain kinds of people who were not like they, I don’t think I’d want to be a Christian either. Really, folks, Christians, like gay people, are everywhere. We are your neighbors, your restaurant servers, your doctors, your bus drivers, your actors, your designers, your playwrights. We are frail human people who are trying to do some good in the world, trying to share the love that God has blessed us with—with others around us. We bicycle, install solar panels, eat healthy, clean our parks. We are trying to make our world a better place. We are not on television talking about our superiority or how we want to condemn our fellow human beings. We don’t separate the sinner from the sin, because we know we are all blessed human creations of a loving God. This is who we are.

Ariel:

Don’t believe what you see or hear about Islam. It’s not about hate or killing; it’s about love and respect for the human being, for oneself, for the plants, the earth, the animals. I think every faith reaches that same consensus, love, we just get there in different ways.

Are you a religiously observant theatremaker? Feel free to answer my questions in the comments!

My boys lighting the Chanukah menorah at my parents’ house, 2006.