People with disabilities make up a significant percentage of the population– by some measures, a full quarter– and yet, despite aggressive, ongoing ableism, we are almost always left out of discussions of diversity and equity in theatre & film. We’re rarely hired and our stories are rarely told– when they are, they’re almost always told by abled people, for abled people, with abled people. Abled people are centered in nearly everything about us.

The centering of abled people routinely takes the form of ableist tropes that present the lives of disabled people through an ableist lens. In these tropes, the disabled body is used as a container for the emotions able-bodied people have about disability.

You’ll recognize all of the following ableist tropes; you’ve seen them all numerous times. I am hardly the first person to write about these, and this isn’t even the first time I’ve written about them. Yet somehow, no matter how often we write or speak about this, ableism never seems to be taken seriously, and our concerns are minimized, dismissed, ignored, or outright rejected. Disabled people need people who live in privileged bodies to do better.

Ten Ableist Tropes to Jettison in 2021:

1. WE ARE NOT SYMBOLS. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen scripts with a disabled person who never appears on stage, only appearing in the play as a topic of conversation, a problem that must be solved by the able-bodied characters. I’ve seen scripts where a disabled person is on stage, but never given any lines or any meaningful action, often partially concealed– back to the audience, or partially behind a screen, for example. In each of these cases, the disabled person is a symbol of something affecting the able-bodied people. When a silent disabled character appears on stage yet is marginalized from the action, the disabled body is minimized, a prop rather than a human being. And those silent roles, removed from all meaningful action, are almost always played by able-bodied actors, which renders disabled people voiceless, powerless, and entirely invisible. The voiceless, powerless, disabled body is framed as a burden, an object of ridicule, an object of disgust, or an object of pity. An object, never a subject.

Our disabilities are not ABOUT YOU. We are not a “symbol of oppression,” a “symbol of willful ignorance,” “a symbol of the voiceless,” “a symbol of the futility of language,” “a symbol for our burdens,” or any of the other dozens of explanations I’ve been given when I point out that the disabled character is reduced to a prop.

2. DO NOT INFANTILIZE US. When you depict your able-bodied characters treating your disabled characters like children, you’re echoing generations of oppression and marginalization we have endured. And these issues are intersectional. When you infantilize a disabled character who is neither male nor white, that infantilization is intensified by the white infantilization of BIPOC and the male infantilization of women, as well as trans, enby, and genderqueer people.

Disabled adults are adults. Needing assistance does not make us children any more than an able-bodied person’s need for assistance makes them children. Everyone on the planet requires the assistance of another person each and every day. Unless you live as a hermit, grow your own food, generate your own electricity, make your own clothing from fabric you craft from raw materials; never use the internet, the postal service, retail stores, roads, healthcare, or sanitation services; never read books, listen to music, watch films, take classes, or have partnered sex, you are being assisted by others.

Adults with disabilities are adults. We have adult problems, concerns, joys, fears, relationships, hopes, ambitions, plans, and desires.

3. WE ARE NOT HERE FOR YOU TO SAVE. One of the most popular tropes is the “heroic” narrative in which an able-bodied person “saves” a disabled person by “curing” them, teaching them something (to walk again! to use spoken language!), or showing them life is worth living. The disabled person is deeply minimized, presented (again) as a problem for the able-bodied person to solve. The disabled character is often entirely reduced to “disabled and sad,”“disabled and angry,” or “disabled and bitter.” Disability is presented as a dragon for able-bodied people to slay while the disabled character sits by passively, and then showers the able-bodied character with gratitude when they are “cured.” The worst part of this trope is that it’s often presented as “the heroic doctor who stops at nothing to find the diagnosis, treatment, and/or cure” when in reality, medical professionals routinely disbelieve us, avoid us, refuse to give us needed tests and medications, misdiagnose us, or give up after their first guess proves incorrect. And this gets much, much worse if you’re also in any of the other groups that doctors treat with the utmost skepticism– if you are a woman, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, poor, or fat.

4. WE ARE NOT HERE TO INSPIRE YOU. You may have already seen this one referred to as “inspiration porn.” We’re not here to inspire you; we’re just trying to live our lives. We have all the same problems you do, plus our sometimes stubborn & disobedient– and beautiful, and sexual, and joyful– bodies. One especially egregious version of this trope is the MANIC CRIPPLED DREAM GIRL. Her illness or disability is always invisible and she’s always played by a thin, conventionally beautiful, young able-bodied white woman. She teaches the able-bodied hero to love, or to find himself, or to “appreciate the beauty of life,” while she bravely “overcomes” her disability to graduate, or travel “one last time,” or enter the big ballroom dance competition or whatever. She then conveniently dies, but not before her Final Inspirational Words, which are, of course, all about HIM. She dies (prettily) and he lives on, eternally inspired. There are many other versions of this trope, such as:

- “NO EXCUSES” (“a nearly worthless disabled person can do this amazing thing, so why can’t you, with all your majestic abledness?”)

- “SUPERCRIP” (“it should be impossible for this disabled person to do this thing, but they are the literal best in the world”)

- “THE ONLY REAL DISABILITY IS A BAD ATTITUDE” (“look how positive this weak and worthless disabled person is; suck up your problems, majestic abled”)

- “HOW CUTE! THEY THINK THEY’RE PEOPLE” (“these poor, useless cripples get one shining moment to pretend to be human through the selfless, heroic work of able-bodied people who staged this event”).

There’s an easy way to depict disabled people doing cool– dare I say inspirational– stuff and avoid sliding into inspiration porn. Just write the disabled character exactly the same way you would write an abled character doing the same thing. Chirrut Imwe from Rogue One is a great example. What prevents him from falling into the “Supercrip” category is the fact that able-bodied characters throughout the series are similarly depicted using the force to achieve seemingly impossible things. Imwe is a valued member of a collective. He has a well-developed personality. His loving, longterm relationship with Baze Malbus is one of the most enjoyable relationships throughout the entire genre. Depict disabled people and our lives as varied and as full as anyone else’s and you won’t go wrong.

5. OUR LIVES ARE NOT ABOUT DISABILITY. OUR PERSONALITIES ARE NOT “DISABILITY.” People with disabilities are wonderful people. We are also petty bitches, selfless heroes, cruel gossips, hardworking activists, ambitious entrepreneurs, excellent parents, terrible parents, and everything else. Becoming disabled didn’t change anything about me. I walk with a cane and have to manage chronic pain but I was the same irreverent, nerdy, overeducated discount Dorothy Parker both before and after I acquired this disability. If “disabled” is your character’s only description, you need to start over.

6. OUR LIVES ARE WORTH LIVING. One of the ways in which able-bodied people comfort themselves in this pandemic is to tell each other, “Most of the people who die have pre-existing conditions.” This is equivalent to saying, “Your life is worth so little that your death is less serious than mine would be.” When a disabled character dies, other characters should not echo this kind of sentiment by saying things like, “At least he’s not suffering any more” unless he was in excruciating daily pain. Sure, there are ways in which disability can limit what we can do, but even if we can’t do a ten mile hike or see a painting, trust and believe our lives are as full of joy and pleasure as yours is. We have spouses and children; we make and consume art; we make and consume food. To quote your aunt’s kitchen wall, we “live, laugh, love” as much as anyone else.

7. DISABILITY DOES NOT MAKE US DIVINE ORACLES. This trope is thousands of years old, and deeply enmeshed in western literature. Sophocles, Shakespeare, and everyone else who wrote prior to the 20th century get a free pass. Yeah, I’m not thrilled about “Now that he is blind, he can REALLY SEE” or “This nonverbal person can literally BLESS YOU,” but no one is seriously proposing that we set fire to classical literature. We’re only asking for an acknowledgment that these tropes dehumanize us and a pledge to do better now that you know. A blind human has no more (or less) psychic, prophetic, spiritual, or metaphysical talents than a sighted human. A nonverbal human is not an “angel.” People with disabilities are people, no more or less oracular than anyone else. Disabled people share this tired trope with BIPOC (the “Magical Negro,” the “Magical Native American,” the “Magical Asian”) and we’re all asking you to do better. How do you know if you’ve written a “Magical Cripple” as opposed to a cool character with special powers? Does the disabled character have any goal, purpose, objective, or concerns other than helping an able-bodied character? If not, it’s time for a rewrite.

8. DISABILITY DOES NOT MAKE US VILLAINOUS. This trope is also thousands of years old, and based in two purely ableist bits of nonsense: “Disabled people are bitter and angry at the world, and their hate and jealousy lead them to commit unspeakable acts,” and “A deformed body reflects a deformed soul.” Again, no one is asking you to detonate every existing copy of Richard III. We’re asking you to acknowledge the issue and pledge to do better in your 21st century work as a writer. Allison Alexander has a great piece on this trope. Read it here.

9. DISABILITY DOES NOT MAKE US INNOCENT. One of the issues widely discussed in medical ableism is the fact that doctors often assume disabled people do not have sex. It can be a struggle to get STD testing, birth control, or useful, sex-positive information. This issue is exacerbated by the portrayal of people with disabilities as innocent, asexual beings. Let’s face it, even people who are genuinely asexual aren’t angelic innocents. No one is. This trope is also expressed as characters with cognitive disabilities who are “too innocent” to recognize abuse or crime, the “cute mute,” and characters with physical disabilities who are automatically assumed to be incapable of evildoing.

10. WE ARE NOT FAKING OUR DISABILITIES. This trope does significant real-world harm. One of the most common problems people with disabilities face is being disbelieved. We’re considered unreliable narrators of our own lives by medical professionals, by our families, by coworkers, and even by random strangers. Nearly every disabled person– certainly every one I’ve ever met– has been accused of exaggerating or outright faking either their symptoms or their entire disability. Ambulatory wheelchair users and people with invisible disabilities are particularly favorite targets of ableist bullying. This trope causes immediate and immense real-world harm whether the character you’re writing is deliberately faking a disability or has a psychosomatic disability that magically resolves when they learn to accept that the Big Accident was Not Their Fault, or when they learn to love life again, or when they learn the true meaning of Arbor Day. (Bonus points for the able-bodied characters smugly smirking behind the Fake Disabled person’s back when he forgets to limp because they have successfully distracted him).

The only possible way around this is including at least one well-rounded, fully developed disabled character. You can argue all you like that people fake disabilities in “real life,” but “real life” also includes far more examples of actual disabled people, so without that counterbalance, your script is just ableist.

Ableism is rampant in playwriting and screenwriting. It’s 2021, writers. It’s long past time to do better.

MORE DISABLED TALENT TO HIRE AND SUPPORT:

Michaela Goldhaber is a playwright, director, and dramaturg who heads the disabled women’s theatre group Wry Crips.

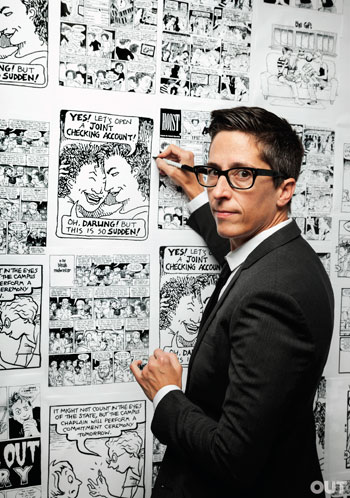

Writer Jack Martin runs the film review website Film Feeder.

Michelle E. Benda is a freelance lighting designer for theatre, dance, and opera. See her portfolio here.

Sins Invalid is a “disability justice based performance project that incubates and celebrates artists with disabilities, centralizing artists of color and LGBTQ / gender-variant artists as communities who have been historically marginalized.” Sins Invalid is run by disabled artists of color.

Access Acting Academy is an actor training studio for blind, low vision, and visually impaired adults, teens, and kids. They offer classes in New York and worldwide via Zoom. Access is headed by actor, writer, director, and motivational speaker Marilee Talkington.

And of course, yours truly. I’m currently available for consulting, dramaturgy, workshops, and classes. You can also become a Bitter Gertrude patron on Patreon.