Jeanette Penley and Will Hand in Lauren Gunderson’s Toil and Trouble. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2012.

Once upon a time, I was ALL ABOUT the new plays. I wrote my dissertation on appropriating and subverting canonical narratives around gender, sexuality, and race in theatre by young artists. I helped found a theatre, the one I head today, whose initial stated goals were all about new plays for an under-40 audience. New plays by emerging playwrights were going to be my life, and, for the most part, they are. I’m hip deep in the new plays community, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Alyssa Bostwick in the PR shot for Impact’s 2002 production of Scab, by Sheila Callaghan. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs.

Even though we were focused primarily on new plays, early on at Impact we started talking about what an Impact Shakespeare would look like. We all loved Shakespeare and we wanted to be able to convey that to our audience, who we believed felt alienated from his work solely due to how it was framed and staged. Founding Artistic Director Josh Costello was very focused on the story of Prince Hal as being analogous to the stories of many young people– working very hard to live up to the scorn and underestimation of the older generation, but able to throw down when the need arose. We began to develop a script that took a little of Richard 2, a lot of Henry 4 Part 1, and a little of Henry 4 Part 2. I was slotted to direct, and we went forward with our first Impact Shakespeare: Henry IV: The Impact Remix. This was 2002.

Falstaff and the tavern dwellers surround Prince Hal in our production of Henry IV: The Impact Remix. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs.

It was how we always did things back then, and still do now: We did something we thought *we* would want to see. Honestly, I wasn’t sure how people would take it. I have a theory about Shakespeare: Because there were no period costumes or period sets as such in the Renaissance, making Shakespeare’s mise en scene essentially contemporary, and because no matter where or when the plays are set, they’re riddled with contemporary references, the plays are written to be staged in a manner contemporaneous to the audience viewing them, and are at their most effective in that staging. I’m not saying that your 1887 staging of Merchant is crap– I’m saying that a period setting adds an additional roadblock to the audience finding a point of entry into the play, and I believe the plays are at their most effective when as many roadblocks as possible are removed.

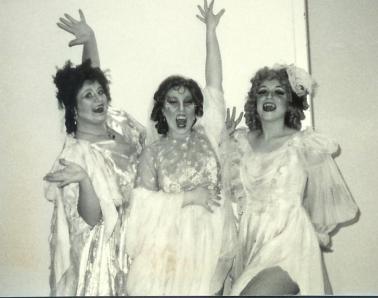

Our Hamlet PR shot by Cheshire Isaacs. That’s Patrick Alparone, Cole Alexander Smith, and me. 2005.

Whenever I talk about this, there are always plenty of angry remarks from people who consider themselves “purists” and believe the plays need to be staged in some kind of period. But I maintain that I’m a purist– I’m preserving Shakespeare’s intent. He staged his work with contemporary sets, costumes, props, music, acting style and conventions. I’m doing precisely the same thing. I’d also like to point out that almost none of these “purists” are staging these plays anything like they were originally staged– in Renaissance dress, with Renaissance accents, Renaissance acting styles (as far as we can reconstruct them), all-male casts with ingenues played by underage boys, Renaissance set and props, Renaissance music played live. Such an experience, while historically exciting and thoroughly badass, is prohibitively expensive, not to mention problematic for other reasons– staging lark and nightingale with a young man and an underage boy in drag could get you arrested now.

In my experience, most “purists” are pleased enough when a play is set in any period of the past, as long as it isn’t contemporary. However, a production set in 1887 is no different than one set in 2013 as far as difference from Renaissance norms goes. In fact, in many ways, we’re closer to the earthy Renaissance in taste and customs than the (at least publicly) prudish Victorians. A production of Lear set in 768 BCE makes very little sense within the context of the play’s narrative (for one thing, the play assumes the main characters can read and write), references, and language, even though the play is ostensibly set then, in Britain’s pagan prehistoric past. Lear is set in 8th century BCE Britain in name only, and the culture of 2013 is much closer to the English Renaissance, where the play’s social structure, references, and narratives were originally located, than prehistoric Britain’s is. So unless they’re advocating for a full-on Renaissance reconstruction, “purists” have no leg whatsoever on which to stand when bitching about modern-dress productions. Let’s leave them aside to work on their production of Coriolanus in Napoleonic dress and move on.

Macbeth. Harold Reid, Skyler Cooper, Pete Caslavka, and Casey Jackson. Photo by Kevin Berne. 2003.

Henry IV: The Impact Remix was an enormous success for us, and was a life-changing event for me personally. I had approached this play with respect, love, and admiration, but without reverence. I believed that my main duty was to tell this story in a way my audience would find exciting and emotionally powerful. It was life-changing for me because it was the first time someone said this to me:

“I hated Shakespeare until I saw this play.”

Jonah McClellan in what will eventually be our Troilus and Cressida poster image. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs.

I’m in the middle of rehearsals for Troilus and Cressida, so, counting that and Henry, I’ve directed 10 plays by Shakespeare at Impact, along with one other classic play (Tis Pity She’s a Whore by John Ford). Every single time we’ve done one of these, at least one person, usually many people, and almost all under 40, say the same thing: “I hated Shakespeare until I saw this play.”

Romeo and Juliet. Pictured: Joseph Mason, Mike Delaney, Reggie White, Jonah McClellan, and Seth Thygesen. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2011.

Am I just a genius director who wields my personal genius to create once-in-a-lifetime Shakespeare experiences? Hahaha no. Not at all. I’m a solid director, but I’m no standout genius. I don’t have LORTs scrambling to fly me out to lay down some King Lear on them. I don’t have some kind of cult following. I’m just a regular director.

The heart of my point here is that ANYONE can do what I do.

It’s exhausting to listen to person after person after person bemoan how few young people like Shakespeare. They blame it on their lack of culture and general boorishness. They blame it on the language. They blame it on the internet, iphones, and video games. They blame it on hip hop. They lay the blame everywhere but where it lies: In boring, lifeless productions.

All of these off-base theories result in “solutions” that are ultimately, of course, unsuccessful. They result in things like that abomination, No Fear Shakespeare. They result in a massively unpopular Romeo and Juliet with “updated” language that was provided as a “translation” of the Shakespeare by Julian Fellowes. “I can do that because I had a very expensive education, I went to Cambridge,” says Fellowes. They result in poorly conceptualized productions that cram popular markers of “youth” such as hip hop or live feed cameras into the production without any regard to the storytelling or any attention paid to the acting style.

But here’s the thing: You don’t need ANY OF THAT to get young people to like your Shakespeare production. A stiff, formal production that doesn’t know what it’s about and privileges poetry over storytelling is not going to be compelling just because you used a hip hop soundtrack or “multimedia” or let people tweet during the show.

I get asked all the time how I get so many young people into our Shakespeares. And again, I want to reiterate that I’m no genius by a longshot, which I think is key to my point that ANYONE can do what I do. The trick is wanting to.

Carlos Martinez and Vince Rodriguez in Titus Andronicus. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2012.

Here’s what I do. Use it or ignore it as you will, but this is the answer to “How do you get so many young people to see Shakespeare?”

I refuse to allow my actors to put on fake British accents or use RP. If you’re actually British, fine. My point is: use the accent you use everywhere else in your life. I don’t scan in rehearsal unless I absolutely have to, and you’d be amazed at how little that is. Unless your actors have deep experience with scansion, it results in stiff, formal dialogue that becomes rote recitation of poetry and loses all sense of storytelling, especially if you make your actors scan all their lines on the first day. I love codes as much as the next nerd, but it’s just not productive if what you’re trying to produce is relevant, passionate, narrative-based storytelling in a six week rehearsal period.

“Talk like you talk; act like you act” is what I tell my actors. “You’re modern people with access to heightened language. Approach this in the same way you’d approach Sarah Ruhl.” When I edit, I privilege narrative over poetry. I find contemporary analogues for every character and situation and stage to that. Staging and costuming provide context that takes care of the language barrier. I approach the plays as if they’re living, relevant stories that tell all the secrets of the human heart in glorious, heart-stopping language instead of historical artifacts or holy writ. Most importantly, I approach the plays as if they’re both FOR and ABOUT the people sitting in my audience.

One of my favorite moments as a director. This group of high school students came to see my Titus Andronicus. They all brought spoons with them and held them up when the pie came out. I collared them after the show for this picture.

It’s not difficult. In fact, it seems to me to be a lot easier than forcing actors into some kind of separate “SHAKESPEARE” space instead of allowing them to just fucking act like they would in any other play. This is part of the reason why I’m mystified by classes in “Acting Shakespeare.” There’s no such thing, or there shouldn’t be. It’s all just ACTING. There’s no need to get precious about it. Shakespeare’s just about the least precious playwright who ever wrote in English. Are these plays the best things ever written in the English language? YES. Do any of the characters know that? NO. Othello has no idea he’s one of the most important characters ever written. All he knows is that his heart is breaking.

If we’re going to go out of our way to teach “Acting Shakespeare,” then what we should be teaching is how to step away from the idea that it’s any different than any other play that uses heightened language. It should be a detox class more than anything else. You’re discovering the language as you say it; it’s the only way you can express what you need to say, focus on your objectives rather than the poetry or states, make your characters real, complex people. Make sure you know the meaning of every single thing that comes out of your mouth, and why you’re saying it. You know: acting.

Marissa Keltie as Desdemona and Skyler Cooper as Othello. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2004.

If you get out of the way, you can give young people the opportunity to love Shakespeare. You have to allow them, though, to love it on their own terms. You’re never going to force someone to love something exactly the same way that you do. Once you hook someone on Shakespeare, it’s a lifelong addiction, and the plays will change for them as they progress through their various life stages. When I first read R&J at 14, I identified strongly with Juliet and was crushing hard on Mercutio– my very first literary crush. Now, as a mother of two teenage sons, the character who resonates the most for me is the nurse, the only person in the entire play who truly loves Juliet for who she is, and therefore the person with the most to lose.

Jon Nagel as Lord Capulet, Bernadette Quattrone as the Nurse, and Luisa Frasconi as Juliet. Ara Glenn-Johanson in the background as Lady Cap. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2011.

I don’t think I have the one definitive answer to what under-40 audiences will like in their Shakespeare. This modern, story-focused approach has worked really well for us, and I’ve seen stiff, scansion-focused, stand-and-declaim productions fail with younger audiences time after time. That’s really all I’ve got for you. I have no doubt that there are directors out there who are working on genius approaches that will excite younger audiences in ways I’ve only dreamed about, approaches that are neither of the two above. All I can say is what I’ve seen fail, and what has worked for me.

If your taste differs, that’s fine. If you want a very poetry-focused, static Shakespeare set in some distant period, that’s great. But don’t bemoan the fact that younger people aren’t flocking to something made to YOUR TASTE.

Tim Redmond as Oberon and Pete Caslavka as Puck. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2009.

I want to address one last thing before I head off to the grocery store while the I WILL MURDER YOU WITH MY RIVERSIDE comments roll in (probs not going to approve those, guys). We get a sizable chunk of OVER-40 people in our audiences as well. Modern stagings won’t push your subscribers out the door. Some of my favorite audience members are retirees. We used to have a group from a local retirement community that regularly came to see our shows and loved what we did. I adored them. They all had a deep knowledge of Shakespeare and honored me with the best discussions after the show. Older people are given the shaft as audience members these days. Everyone complains about them and no one seems to value them. I *LOVE* having them in our space. They’re smart, sophisticated viewers who have been seeing shows since before we were born, and have insights and opinions well worth listening to. People who look down on older audience members don’t know what they’re missing. And bear in mind that 75 isn’t what it used to be– that 75-year-old woman in your front row was in her 20s, naked, at Dionysus in 69. So don’t judge.

Marilet Martinez as Mercutio with Miyuki Bierlein as Balthasar underneath. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2011.

But honestly, I don’t think younger people like Shakespeare or hate Shakespeare or are indifferent to Shakespeare in any sizably different proportions than any other demographic. The issue is that we believe that young people SHOULD like Shakespeare, because it’s “good for them,” but we are much more likely to leave older people and their tastes alone. There’s no question that the average American middle-aged man would rather watch football or porn (especially in Utah— high five, Mormons) than Shakespeare. However, we don’t, by and large, bemoan the fact that that football-loving, porn-watching BYU facilities manager doesn’t like Shakespeare in the same way that we bemoan the fact that those football-loving, porn-watching BYU students don’t. For some reason, their disinterest is posited by the culture as dire, while the facilities manager’s disinterest is seen as his due– just his taste.

Dennis Yen as Adam and Miyaka Cochrane as Orlando. Photo by Cheshire Isaacs. 2013.

I wouldn’t worry about young people not loving Shakespeare. Shakespeare is unstoppable. Those stories and that language contain an irrepressible power and beauty, and there are plenty of young people who will find them, especially if you don’t hide them behind a screen of fake accents and stiff delivery. Let them breathe. They will reward you.