Source: diversitytoday.co.uk

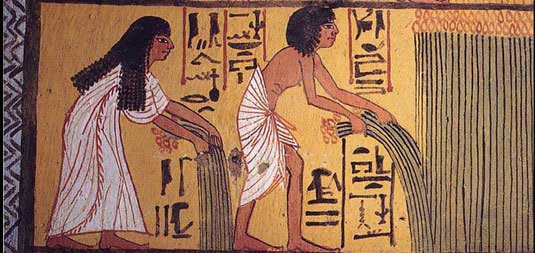

Harvesting grain in ancient Egypt

“Ceres, Goddess of Agriculture” by Emily Balivet. See more of her work and purchase prints here.

Source: diversitytoday.co.uk

Harvesting grain in ancient Egypt

“Ceres, Goddess of Agriculture” by Emily Balivet. See more of her work and purchase prints here.

Our “canon” has deliberately shut out women and people of color for a great many generations. Until fairly recently in western history, it was very difficult for women and people of color to become playwrights (lack of access to education being a significant bar), and for those who were playwrights, it was very difficult to get produced outside of certain theatres. Even if produced, the work of women and people of color was rarely considered “important” or “universal” enough to be included in the kinds of awards, articles, books, and university courses that created what we consider to be the “canon.” Plays that were considered “universal” reflected specifically white and male points of view; plays that differed from that were considered specific to a cultural subgroup rather than “universal” in the vast majority of cases. Even today, most works in a traditional survey course are written by white men while “Black theatre” is its own category, often represented by a single play. In my undergrad education, that play was the short piece “Dutchman” by Amiri Baraka– we didn’t even read a full-length play. “Asian Theatre,” “Chicano Theatre,” and “Feminist Theatre” are still often brief mentions as classes move directly to more important, “mainstream” writers such as Sam Shepard and David Mamet, with Caryl Churchill the lone female voice in an otherwise very male reading list.

Scholars and theatremakers have begun the process of interrogating the formation of the canon, as well as reframing the works we consider “canonical” within their specific sociohistorical context rather than continuing to pretend these works are “universal.” This is vital work.

You only get answers to the questions you ask. Scholars and theatremakers are asking new questions about “canonical” works and the formation of the “canon.”

When we stage canonical work, we have two choices. The first is what is mistakenly referred to as the “purist” approach. This approach holds that works should be preserved untouched, performed precisely as they were first performed. There’s some educational value in performing work in historically accurate ways– at least as far as we can reconstruct that level of accuracy. Those who advocate for this approach believe they are defending the “playwright’s intent,” which means they somehow believe that their interpretation of the “playwright’s intent” is the only accurate one. These people are, in my experience, overwhelmingly white and male, and, as such, have been taught from birth that their experience of the world is universal, and their interpretation of the world and its processes and symbols is “correct,” so it’s not entirely surprising that they believe they are the only ones who understand the “playwright’s intent” and can therefore separate what is a reasonable interpretation of a work from page to stage from what is a “desecration.”

There are many problems with the purist approach. First of all, no one knows the playwright’s intent if the playwright, as is the case with most canonical plays, is dead. Even if the playwright wrote a 47-paragraph screed entitled “Here Is My Intent: Waver Not Lest Ye Be Tormented By My Restless Spirit,” no one knows what the playwright’s intent would be if he had knowledge of the cultural changes that occurred after he died. The audience for whom he wrote the play– the culture that understood the references, the jokes, the unspoken inferences; the culture that understood the underlying messages and themes; the culture to whom the playwright wished to speak– is gone, and modern audiences will interpret the play according to their own cultural context. Slang terms change meaning in months; using a 400-year old punchline that uses a slang term 90% of the audience has never heard seems closer to vandalizing the playwright’s intent than preserving it. Would Tennessee Williams or William Shakespeare, masters of dialogue, insist that a line using a racial slur now considered horrific still works the way he intended? Still builds the character the way he intended? It seems dubious at best, yet this is the purist’s logic. The playwright’s intent on the day the play was written, the logic goes, could not ever possibly change.

It’s important to continue to study these works unchanged. We must not forget or attempt to rehabilitate our past. But to claim that lines written decades or even centuries in the past can still work the way the playwright originally intended is absurd.

We have begun to understand that the “canon” and its almost exclusively white male point of view is not “universal,” but is a depiction of the cultural dominance of a certain type of person and a certain way of thought. We have begun to re-evaluate those works and the “canon” as a whole as part of a larger historical narrative. This is why it is of great artistic interest to stage “canonical” work in conversation with the current cultural context.

When staging, for example, The Glass Menagerie in 2017, one must consider the current moment, the current audience. We can choose to present the work precisely as it was presented in 1944 as a way to experience a bygone era, or we can present the work in conversation with its canonical status, in conversation with our own time, in conversation with the distance between its era and our own, in conversation with the distance between the playwright’s intent and the impossibility of achieving that intent with a modern audience, simply due to the fact that too much time has passed for the original symbols, context, and themes to work the same way they once did.

What does The Glass Menagerie— or any canonical work– mean to an audience in 2017? What can it mean? What secrets can be unlocked in the work by allowing it to be interpreted and viewed from diverse perspectives? What can we learn about the work? About the canon? About the writer? About ourselves?

The meaning of any piece of art is not static. Whether the piece of art is a sculpture created in 423 BCE or a play written yesterday, the meaning of any piece of art is created in the mind of the person beholding it in the moment of beholding. The meaning of each piece changes with each viewing, just as the meaning of what we say is created in large part by the person to whom we’re saying it, which is why we can say “Meet me by the thing where we went that time” to your best friend but need to say “Meet me at the statue across from the red building on the 800 block of Dunstan” to an acquaintance. To insist that there is one “correct” meaning– always as determined by a white male– is to deny the entire purpose and function of art. You cannot create a “purist” interpretation without the play’s original audience in attendance. The closest you can come is a historical staging a modern audience views as if through a window, wondering how historical audiences might have reacted, or marveling at the words and situations historical audiences found shocking– or did not. How many audiences in 2017 understand Taming of the Shrew as a parodic response to the popularity of shrew-taming pieces? Shakespeare’s audience is gone and the cultural moment to which he was responding is gone, so the possibility of a “purist” staging is also gone.

This is 2017. Our audiences live in 2017. It’s insulting to them to present a play written generations in the past as if nothing about our culture has changed since then, as if a work of genius gave up every secret it had to give with the original staging, as if art has nothing whatsoever to do with the audience viewing it.

We know better. Art lives in our hearts and minds, whether those hearts and minds are white and male or not.

A marble bust of Julius Caesar dating from the 1st century CE

The Public Theatre is staging Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar as part of its annual Shakespeare in the Park, and hauling out that most overdone of concepts: Julius Caesar is POTUS! They’re all in suits! It’s AMERICA! This is exactly why I never directed Julius Caesar— it’s just about the only approach that makes sense in modern America, and it’s been done approximately infinity times. The Public’s approach is about as controversial, given every past production of the last half century, as your niece’s school production of “Transportation and You” where she plays a Happy School Bus.

You were great, McKayyLyee! (Source: Toddlerapproved.com)

I’m not saying the Public’s production won’t be great theatre. I’m saying that concept is not exactly unique or controversial. And yet, because this is Trump’s America, this old-as-the-hills concept is suddenly Not Acceptable, and both Delta and Bank of America pulled their funding from the Public, joined shortly afterwards by American Express.

THAT. IS. INSANE.

Has no one read Julius Caesar? I mean, obviously Trump hasn’t since he can’t make it through an intelligence briefing unless “TRUMP <3” is inserted into every other sentence. I mean– has anyone complaining about this concept ever read (or seen) the play? Anyone at Delta, BofA, or AmEx? The play does not condone the murder of Caesar. While Caesar’s desire to be king, his arrogance, and his deafness to criticism all threaten democracy, murdering Caesar results in disaster. The Public released an excellent statement, which says, in part

Our production of Julius Caesar in no way advocates violence towards anyone. Shakespeare’s play, and our production, make the opposite point: those who attempt to defend democracy by undemocratic means pay a terrible price and destroy the very thing they are fighting to save. For over 400 years, Shakespeare’s play has told this story and we are proud to be telling it again in Central Park.

In 2012, the Guthrie, another high-profile theatre, staged Julius Caesar with (unsurprisingly) the same concept, but of course POTUS at the time was Obama. Delta funded that production without a peep of complaint.

So what is this hypocrisy about? Why is Delta pretending to be offended about the Public production? Why is anyone pretending to be offended by this production, considering they’ve never been offended by that oft-used concept before?

William Sturdivant and Sid Solomon in the Guthrie’s 2012 Julius Caesar. (Photo: Heidi Bohnenkamp)

Here’s the paradox: Trump’s arrogance, desire to rule like a king, deafness to criticism, and complete lack of tolerance for anything other than adulation mirror Shakespeare’s Caesar, yet to say so openly is dangerous exactly because it is true– Trump will act like a king and use the power of his office and fame to retaliate.

Trump relentlessly abuses his power. He has no qualms about using the power of his fame and, more importantly, using the power of government to quash those who criticize him or disagree with him. You’d think that was unconstitutional, and that Okieriete Onaodowan placed checks and balances in the Constitution specifically to correct for that, and you’d be right, except the GOP-controlled Congress shows no signs of reining in Trump’s dictatorial behavior, and are clearly willing to sell out our entire democracy for something as tawdry as a tax cut for the wealthy.

Congress won’t move to stop Trump’s democracy-destroying behavior unless doing so retains or increases their popularity. Trump’s approval rating is quite low, but never dips below 35%, and that is a substantial percentage of voters who seem quite content to believe that the media, people of color, feminists, Democrats, Mexicans, LGBTQ people, Muslims, and the “coastal elite” are quite literally their enemies instead of their neighbors. Fed a constant diet of fear and hatred by the right-wing media for the past 20 years, they’re happy to allow the GOP to decimate every legal protection we have in the mistaken belief that it hurts their “enemies,” and the GOP Congress in turn is happy to allow Trump to abuse his power all he likes as long as he signs whatever they put in front of him. Our Rome applauds our Caesar’s abuses of power while our Senate winks.

Meanwhile, those of us who can see the damage being done to our democracy by these abuses of power are left wondering what to do about it since no one who is tasked with protecting us is actually interested in protecting us (apart from the courts, and Trump is trying hard to change that). Whatever the answer is, just as Julius Caesar says, it’s not violence. Having a bunch of Senators murdering Trump on the Senate floor (although arguably a real ratings getter) would eliminate a threat to democracy while actually threatening democracy itself. The cure is the same as the disease. It’s sociopolitical homeopathy, and just like real homeopathy, it’s costly and it doesn’t work.

“Violence is not the answer” is an important message to get out to a culture that is experiencing a dramatic upsurge in politically-motivated violence and violent rhetoric. Yet this is the message that’s considered “too offensive” because it depicts the violence it then goes on to condemn.

The damage Trump is doing to our democracy has already been done if companies are pulling funding from the Public’s Julius Caesar out of fear of Trump and his followers retaliating against them for speaking the truth about Trump’s similarities to Shakespeare’s Caesar and stating “Even though he threatens our democracy, violence is not the answer.”

Can we recover from the damage Trump has done when so many Americans are content to allow it as long as they can continue to believe it hurts a group of people they have been taught to hate? Can we recover from the damage Trump has done if our elected officials evacuate their constitutional duty to oppose that damage?

I have no idea if we can recover as a nation. I have to hope that we will, and that midterm elections will turn the tide. Until then, all I know is that I’m sending a donation to the Public Theater. If Delta, BofA, and AmEx won’t help to pay those actors and techs, WE WILL.

UPDATE: Classical theatres across the country are receiving threats from conservatives angry about this one production. Please support your local classical theatre! If you can’t donate, even a note of support would be helpful.

photo by Tom Hilton

I keep running across white women saying things like, “I’m never seeing any film or play that doesn’t pass the Bechdel test ever again!”

This statement epitomizes the problem with white feminism.

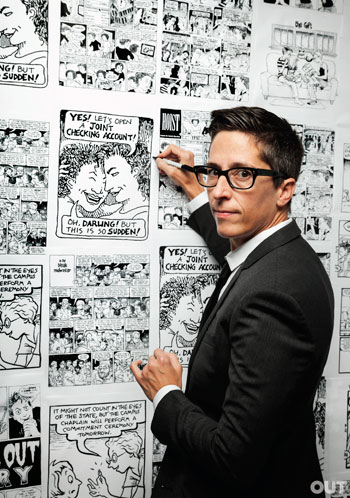

First, a quick definition of the Bechdel test, invented by amazing writer and comic artist Alison Bechdel, known for the long-running comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For and her memoir Fun Home, which she turned into a Tony Award-winning musical. Just in case you weren’t already convinced she’s a genius (and I have been since the old DTWOF days), she was a 2014 recipient of the MacArthur “genius” grant.

Alison Bechdel. Source: Out Magazine.

The “Bechdel test” is a metric she created in 1985 in a DTWOF strip to evaluate female representation in films. In order to pass the Bechdel test, a film must have two female characters who have at least one conversation that is not about men. It sounds surprisingly basic, yet the vast preponderance of films cannot pass the Bechdel test.

The Bechdel test becomes tricky when applied to theatre. For example, it immediately eliminates all solo performance and all male/male and male/female two-handers, regardless of content.

And this is exactly my issue with the Bechdel test being used as a basic metric of acceptability in theatre– it ignores both content and context. It ignores intersectionality.

Let’s take two examples. The first play, written by a middle-aged white man, is about four wealthy white women discussing their problems and lives while at various brunches in upscale New York eateries. The main topics of conversation are their wealth and whether the sacrifices they made to obtain that wealth were worth it. The central narrative is one character revealing she has lost most of her money and must now live outside Manhattan. This play neatly passes the Bechdel test.

The second play, written and performed by four young Black men, is about their experiences growing up in Oakland. The main topics of conversation are police violence and racism. The central narrative is the loss of their friend, murdered by police while unarmed, driving home from work at a local elementary school, the same school where all five friends met. This play does not pass the Bechdel test.

If the goal of metrics like the Bechdel test are to hold artists accountable for the work we create, insisting on work that resists cultural marginalization and works for inclusion, the Bechdel test is not enough. It is not enough to fight for the inclusion of women and ONLY the inclusion of women. Insisting that a play about privileged white women is so deeply, intrinsically superior to a play about Black men that we can issue a test to “prove” it is counterproductive to every diversity goal we have. We’re issuing a test that by design marginalizes men of color.

We need work that passes the Bechdel test, and we need it badly. But we cannot use that test as a metric for the acceptability of all work.

Kamal Angelo Bolden as Chad Deity in The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity in the Victory Gardens/Teatro Vista co-pro in Chicago, 2009. Photo: Chicago Theater Beat

We live in an intersectional world, and issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion must be addressed intersectionally. Yes,we must fight for the inclusion of women in our narratives, but we must also fight for the inclusion of other marginalized groups. When we refuse to do so– when we announce that all plays must pass the Bechdel test in order to be acceptable, as I have seen so many white women do– we fail. We become “white feminists,” content with centering ourselves while ignoring other marginalized groups.

To state that you will never see a play that does not pass the Bechdel test is to state that Crimes of the Heart, In the Boom Boom Room, and Five Women Wearing the Same Dress are intrinsically important and worthwhile, while Topdog/Underdog, The Mountaintop, The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity, The Year Zero, Mambo Mouth, and Twilight: Los Angeles 1992 are not worth seeing.

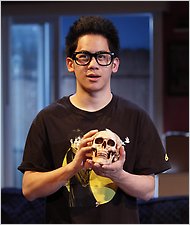

Mason Lee in the Off Broadway production of The Year Zero, 2010. Photo by Joan Marcus.

The Bechdel test even fails at what it was purportedly designed to do. Many films steeped in misogyny pass. “Lesbian” pornography made for male consumption passes. Most Disney princess films pass. The Bechdel test, I have to believe, was never meant to be an iron-clad metric.

I don’t know Alison Bechdel, but I consider the Bechdel test excellent social commentary, not a call to action. It’s meant as criticism, to make a point about how few films have female characters with objectives of their own. It’s meant to point out how few films present women as human beings rather than as events in the lives of men.

We cannot use the Bechdel test as the sole metric for acceptability. The examination of our work and its resistance to, and participation in, systems of oppression is a complex process, not a three-point test.

Even issuing a test is a classic white gatekeeping maneuver. White liberals are always looking for clear-cut guidelines to make us instantly “not racist” or “not sexist,” and we excel at creating oversimplified litmus tests that prove we are the Most Woke and everyone else is Doing It Wrong.

not how it works

You can’t fill out a form with your credentials (“voted for Obama,” “watched Jessica Jones,” “smiled hard at Black guy on the street”), mail it in with a self-addressed stamped envelope to the Women’s Studies department at Howard and then just wait for your NOT RACIST OR SEXIST certificate to roll in. There’s no “Woke White Person” checklist.

There’s no test.

Fighting for diversity and equity in theatre is a complex, multifaceted process that involves the stories we tell and how we tell them, including who tells those stories and who’s in our audiences, who are the decision-makers and gatekeepers, where the funding comes from, and so much more. As tempting as it is to get a definitive ruling on what is “resistance theatre” and what is “collaboration theatre,” that fact remains that each piece of theatre we make will have facets of resistance and facets of collaboration, and all we can do is commit to the process of examining our decisions in both the work we make and the work we consume as thoroughly and realistically as possible. It’s never going to be as simple as only going to shows with The Gold Star of Bechdel next to their titles. Fighting systems of oppression requires more of us, much more.

Commit to the process. Continue to love the Bechdel test for what it is– an eye-opening way to examine narrative that sometimes works and sometimes does not, but can be an effective tool when used correctly. It was one moment of genius in a long career of genius moments for Alison Bechdel, but cannot be– and was never meant to be– the sole, definitive arbiter of acceptable work.