I recently received a submission of a play we rejected not two months ago. The playwright attached it to an email directly to me (bypassing my new Literary Manager, the wonderful Lynda Bachman), which is fine. I generally just forward those to my LM unless I have a personal connection to the playwright or to the person sending me the play. But this email was different, and I hesitated long enough to read it, and, unfortunately, respond.

The playwright decided she was going to resubmit her play so soon after its initial rejection because she noticed that I had “replaced” my literary manager (our outgoing LM, Steve Epperson, left to pursue other career options, not because he was “replaced”), and believed that I would better understand her play because I was a woman.

You would imagine in that case the play would be about something specific to the female experience, but it was about writers and mythological characters. My vagina and I read the play together and were able to ascertain almost immediately why Steve had rejected the play: It had technical requirements that were outside of the physical capabilities of our idiosyncratic space and, more to the point, it was poorly written. The playwright showed some promise, to be sure, but the play had all the earmarks of a young writer’s early work– undifferentiated character voices, derivative narrative, clunky dialogue, privileging the “Big Idea” over the stories of the characters.

I gave her some feedback that was honest without being assholic (so I believed, anyway) and encouraged her to work on her craft and continue submitting to us. And of course she responded angrily, which is exactly why we don’t give feedback in rejection letters, even if we could. We receive between 300-400 unsolicited submissions a year, and we just don’t have the womanpower/manpower/level ten cleric power to give feedback to all of them. Then there’s the very real issue that not all feedback is created equal, and feedback you get from some random theatre company that has never met you and has no idea what your vision is or what you’re trying to accomplish with the play will be almost always useless (unless what you’re after is why that one specific company rejected your play).

And I really do understand the anger. It’s hard to be rejected, and playwrights are rejected over and over and over. I can understand why a playwright, in order to stay sane, would look for reasons like, “They rejected me because the LM doesn’t understand my work” in order to avoid having to think “Perhaps my play is not ready to be professionally competitive.”

Part of the problem is that theatres almost NEVER speak honestly to playwrights about why their work is rejected. So I’m going to, right now. If you’ve ever received a rejection letter, the reason is one or more of the following, I guarantee it.

1. Your play is actually awesome, but not right for the company. We have very real limitations that we cannot avoid, such as tech limitations, space limitations, or financial limitations. Some of us have resident actors, and we need shows with solid roles for them. Perhaps your play is outside the theatre’s aesthetic, or outside the theatre’s mission. Maybe your play doesn’t fit well with the plays already selected for the season– perhaps it’s too close in tone or feel to the play already locked into the slot before or after the one for which it’s being considered. Perhaps another theatre company in our area just did a play almost exactly like yours. You would be AMAZED at how many awesome plays get passed over for practical reasons like these. It happens to me multiple times, every single season.

1. Your play is actually awesome, but not right for the company. We have very real limitations that we cannot avoid, such as tech limitations, space limitations, or financial limitations. Some of us have resident actors, and we need shows with solid roles for them. Perhaps your play is outside the theatre’s aesthetic, or outside the theatre’s mission. Maybe your play doesn’t fit well with the plays already selected for the season– perhaps it’s too close in tone or feel to the play already locked into the slot before or after the one for which it’s being considered. Perhaps another theatre company in our area just did a play almost exactly like yours. You would be AMAZED at how many awesome plays get passed over for practical reasons like these. It happens to me multiple times, every single season.

WHAT YOU CAN DO: Hang in there. Believe me, when we find a gem that we can’t stage, we’re whoring it out to other companies trying to get someone else to stage it. I’ve done that with tons of scripts. I just sent four out today, in fact, plus two last week. You can also research theatre companies online to see what kinds of plays they do, what their missions are, and what their aesthetics are in order to better target your submissions. If your script is truly awesome, it will eventually find a home. Be patient, especially if it’s very demanding to produce. This can include things like a big cast (very expensive) or difficult tech (requiring two levels springs to mind as a common problem that can be difficult both physically and financially) or challenging casting (such as, an actor of a very specific type who can sing while playing a portable instrument, or actors with specific physical skills, such as contortionists). But even a very demanding play will eventually find a home if it’s truly awesome– look at Kristoffer Diaz’s The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity, or Aaron Loeb’s Abraham Lincoln’s Big Gay Dance Party. So hang in there.

2. Your play is not well-written. The most common problems are all the ones I state above (undifferentiated character voices, derivative narrative, clunky dialogue, privileging the “Big Idea” over the stories of the characters), plus things like lack of continuity, or “therapy plays” (where the playwrights are less interested in telling a story and more interested in working out issues with their mother/ex-wife/abuser/etc). Playwriting is fucking HARD, and even good playwrights write bad plays from time to time. Artistic Directors and Literary Managers will never, ever tell you your play is just not very good because we’re afraid of hurting your feelings and destroying a relationship. Playwrights who start out sending bad plays often end up, after getting some training and/or experience, writing GOOD plays, and we want access to those good plays.

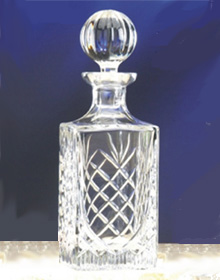

Look on the bright side! At least you didn’t write THIS.

WHAT YOU CAN DO: Work on your craft. Read this book. Read every play and see every play you can. See more theatre than film or TV. Yeah, a lot of film and TV are high-quality, and you can get good ideas from filmmakers and television writers, but theatre is a different animal with different demands. Learn how to feed it.

3. The odds are insane. My tiny company, as I said above, gets 300-400 unsolicited submissions a year to fill 3 slots. I recently spoke to someone who works at a large theatre that focuses on Shakespeare and does not accept unsolicited submissions, and she said they still receive about 200 annually. Someone else in that conversation said her theatre gets 900 a year. Your play is one of hundreds and hundreds out there. There are easily 100 plays for every production slot in the country, if not more. Let that sink in: Every single open slot in every single theatre in the country easily– EASILY– has 100 plays competing for it. In order to beat the odds, your play not only has to be VERY good, but it also has to be the right play at the right time for the right company.

NEVER TELL ME THE ODDS.

Luckily for you, you live in the WORLD OF TOMORROW, where submitting a play is as easy as hitting “send.” Take a moment to think of the poor playwrights of yesteryear (15 years ago) who were copying out scripts at work when their supervisors were in a meeting and having to mail them out to theatres at $2.50 a pop if they didn’t work in a company with a mailroom (I remember getting submissions from Lehman Brothers regularly). The flip side of the newfound ease of the submission process is that we’re all getting hundreds and hundreds of scripts, all the time. Even if your script is fantastic, is it better for THAT THEATRE at THAT MOMENT than the other 412 the theatre will get that year? Maybe the AD has done three comedy-heavy seasons and is considering moving to a more drama-heavy season the next year. Maybe the theatre is hoping to work with a specific director and looking for scripts that will appeal to her. Or perhaps this director is already involved in the selection process. Maybe this director had a recent personal experience that increases her interest in a certain topic, and although your play is just as awesome, the play submitted right after yours is about exactly that topic. The point is: You don’t know. The variables are endless, and the competition is just insane. When I’m in season planning season (ha) in Dec/Jan, I’ll sit at my computer and open file after file after file, reading plays for hours every single day. I don’t even glance at the name of the playwright or the title of the work unless I’m already interested in moving it up to my contenders file, or if I’m sending an email to my LM indicating which ones to reject. It’s truly crazy how many plays we get, and we’re the smallest dog on the block.

WHAT YOU CAN DO: Again, hang in there. Target your submissions. Develop relationships with ADs and LMs. I have personal connections with a few playwrights who know they never have to go through our formal submission process, but can send plays directly to me, AND I WILL READ THEM. They go directly into my personal season planning folder. I know these playwrights are creating quality work and I want to get my hands on it. There are playwrights whose work I have rejected numerous times because it wasn’t the right play for us at the right time who know they can submit directly to me, because despite the fact that I haven’t produced them, I believe in their work and think they’re superstars. If I can’t produce the script for one reason or another, often I’ll send it to someone who I think might be interested. I recently fell in love with a playwright who has a script I can’t produce, and I’ve been sending her play all over the place. ADs and LMs are your CHAMPIONS, not your enemy.

4. Content. This one is rare, but it does happen. We reject plays with misogynistic, anti-Semitic, racist, or homophobic content. We rejected the play that was made up of scene after scene of child pornography.

I repeat: SCENE AFTER SCENE OF CHILD PORNOGRAPHY. ::shudder::

What we’d never do is reject a play because its content is too “radical” or too “challenging of the status quo” or what have you. We didn’t reject your play because we “weren’t ready” to have our “minds blown” or because we’re trying to “silence” your “anti-patriarchal dissent.” We produce in Berkeley, you know? Nothing is “too radical.” That said, I can imagine a theatre in American Fork, Utah rejecting a play that espouses the kind of liberal values Berkeley takes as a matter of course. So who knows? I can’t speak for the theatres in Beaver County, Oklahoma. Would I reject a play that espouses conservative values? I’ve actually never received a play that was, for example, anti-marriage equality, and of course I wouldn’t stage it if I did, so I suppose the answer is a provisional yes. Artists on the whole are a liberal-leaning bunch, so I don’t get plays about why we should fund a tax cut for the wealthy by eliminating food assistance for poor children, but if I did, it’s likely we wouldn’t stage it. So no need to send it to me, David Mamet. But yes, playwright in Utah who recently contacted me with a concern that his play might be too controversial, I do want to read your play about a transgendered person. I want to read it so hard! Theatre is like 99.99% cisgendered, so anything that can address that lack of visibility automatically interests me. I can easily see, though, how that view might not be shared by an AD in, say, Kansas.

WHAT YOU CAN DO: If you’re writing plays with misogyny, anti-Semitism, racism, homophobia, or child pornography, stop writing plays. For the rest of you, target your submissions accordingly. Online research is your friend. Check out a theatre’s production history. Follow the AD or LM on twitter. There are lots of ways to ascertain which companies might be a good fit for your work.

Again, I want you to remember that there are over 100 plays for every production slot in the country. I have to pass on plays I adore every single season. I have 3 slots for new plays, and we get between 300-400 unsolicited submissions, in addition to the ones I headhunt. The unfortunate truth is that the odds are overwhelmingly against you.

HOWEVER. We are on your side. I’ve dedicated my life to championing new work, and there are hundreds just like me out there. WE BELIEVE IN YOU. That’s why we chose this field. You don’t acquire wealth or power producing nonprofit theatre. Far from it. Even the highest-paid LORT ADs still make a fraction of what they’d make in a similar corporate job. (My brother laughed out loud when I told him with awe how much the head of a local LORT makes. Having spent my entire career in theatre and academia, I had no idea these salaries were so small compared to the corporate world.) We didn’t start these companies because we thought we’d become wealthy and powerful. We started these companies FOR YOU. If I could stage 20 plays a year, I would. I believe in you and your work. I wake up in the morning and answer emails and hire directors and schedule auditions because your work deserves to be seen.

Remember that we’re on your side. Remember that a rejection is not always a comment on the quality of your play, and even while you’re reading that rejection, I may very well be sending your play to another AD. Remember that there are so many of you out there that 99 plays must be rejected for every 1 that gets accepted. And always, always remember that we’re here because we love you and think you’re superstars.

So hang in there. Try not to let the rejections get you down. Work on your craft. Create relationships with ADs and LMs, a simple thing to do now that you can facebook friend us or follow us on twitter. (I found an amazing play we’re producing next season through a friendship I developed with a playwright on twitter.) Target your submissions. And KEEP AT IT. We need you, OK?