Art by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh. More of her awesome work at: http://www.tlynnfaz.com

So lots and lots of people who are cooler than I am have written about street harassment. Whenever I post about street harassment on facebook, I get dogpiled with comments– always from men– defending the behavior, or saying things like (and I quote):

“You should take it as a compliment!”

“That doesn’t happen in [city name].”

“That never happens in [type of place, such as subway, mall, universities].”

“I’ve never seen that happen.”

“Only men of certain ethnicities do that.”

“How else are we supposed to meet women? Give us a break!”

…….and the like. I have been told by men, in no uncertain terms, just how wrong I am every single time I’ve ever spoken up about this issue. Every. Single. Time. I see you, men who are limbering up your fingers to tell me I’m just a dumb girl, or a feminazi, or that I just don’t understand, or that I’ve made the entire issue up because duh women do that all the time. Hold up. Read the rest of the article, click on the hyperlinks and read those, and if you still feel like telling me what an asshat I am, I promise you I will read your comment with a serious look on my face THROUGH THE WHOLE THING.

This is what my serious face looks like . . . IN MY IMAGINATION. And please stop telling me I’m Simon, not Zoe. I ALREADY KNOW.

The small area of the Street Harassment Monster I want to tackle right now is the, “Smile, baby! Why don’t you smile? You’d look so much prettier with a smile on your face.”

If you are approaching a stranger with any variation of the above, you are behaving like the human embodiment of painful rectal itch. Here’s why.

Accosting strangers on the street is uncool. In addition to being fucking annoying, it makes women feel unsafe. We have no way of knowing what you’re going to do. I was pushed, HARD, to the ground, at an ATM because I refused to acknowledge a strange guy who was demanding that I smile at him. If our responses to your demands for attention are not to your liking, many of you immediately escalate the encounter to verbal or even physical abuse. We have no way of knowing whether you’re just going to walk away or whether you’re going to follow us down the street yelling, “Fuck you, you stuck-up bitch. Who do you think you are, fat bitch? Don’t you ignore me, bitch,” grab us by the arm, pin us up against a wall, or surround us with jeering companions who threaten to rape us. WE DON’T KNOW WHAT YOU WILL DO. It’s scary. Stop it.

Is it unfair that you, who believe you are a Nice Guy, have to curtail your behavior because other men are behaving like worthless chumpbuckets? Maybe, maybe not, but it’s MUCH more unfair that you’re forcing a woman into an interaction that she knows has a very real chance of ending in verbal or physical abuse.

You have no idea why she’s not smiling. Did she just get the news of a death in her family? Lose her job? Is she having painful menstrual cramps? Did she just kill a strange man who harassed her on the street and is worried about doing it again now that she’s tasted blood? Demanding that a woman construct a cheerful look on her face simply because you demand it is to ignore the fact that she is a person with a life, just like you are. You know NOTHING about that life, and therefore, you know NOTHING about her emotional state. Back off. Actually, back off and read this.

You are not entitled to cheerful interactions with women on demand. Why do you think it’s OK to make random demands of women on the street? You are not our toddlers. Do not demand juice boxes, smiles, or attention from women you do not know. This is what toddlers do. This is why mothers are exhausted: constant demands for attention. Before you demand that the woman you see walking towards you (or are following, ew) force a smile on her face, remember that you are the third man who has demanded her attention in the last 20 minutes. She just wants to walk down the damn street. If she wanted a toddler, she’d have one. If she has a toddler and you harass her with “Smile for me! Don’t forget to smile!” she is now, thanks to Olympia Snowe and her outgoing gift to American women everywhere, The American Patriot Mothers for American Patriotic Heritage Act, legally entitled to give you a roundhouse kick to the temple.

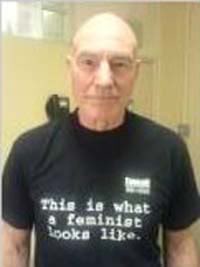

No, your attention is not flattering. I’m just going to leave this here in case you’re wondering what women think of your commentary and/or demands.

If you think this behavior is OK, remember that there are quite literally millions of men all over the world who agree with you, and many of them will start harassing your daughter once she hits middle school. They harass your wife. They harass your little sister.

All we’re asking is that you remember that women are people. All we’re asking is that you treat women on the street with the same respect you’d treat your daughter, your mother, or a heavily armed level 20 dwarf fighter.