What I wish I had been able to do this week

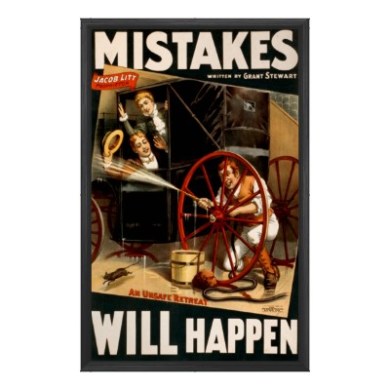

I haven’t posted in awhile because I’ve had a crazy busy week. Among a few other magical surprises, my company lost an actor, and it turned out that, because the show was a commission being built specifically around this actor and his particular talents, we couldn’t, hard as we tried, recast non-AEA, so we had to scramble to fill the slot with something else. We can’t use an AEA actor because we can’t afford the lowest-tier contract right now, and we’ve used up all our waivers.

And I hear all you people outside the Bay Area saying “What?!” Yes, in the Bay Area, a company only gets a few waivers to use in their first few years of existence, and then can never use another waiver ever again for any reason world without end.

Before I go any further, let me lay down a few piles of facts: I’m very pro-union. My grandfather was a forklift driver and my husband is a middle school teacher. I know what unions are for and why they’re important, and union busting is something I cannot abide. I would never cross a picket line. I think unions are vital.

I remember my mother refusing to buy grapes and making sure we knew why.

Secondly, I wouldn’t have any reason to complain about AEA if I didn’t follow its rules. I left an entire job on the table in part because I couldn’t handle willful violations of AEA contracts. I didn’t want to be associated with that, and I didn’t want to have to fight like a cornered wampa over every single contract. I could easily eliminate my problems by just violating contracts and hoping to fly under the radar (“We’ve never been caught,” I was told), but I won’t do that. For one, I think I WOULD get caught, and, much more importantly, it’s not right.

So here’s my problem: In the Bay Area, at least, AEA operates under a fundamental misunderstanding of its own market.

AEA exists in a bizarre context. There are hundreds of actors working in commercial theatre like big Broadway musicals, touring companies, and the like. These commercial enterprises would happily work these actors to death, collect wagonloads of cash from $200 tickets and 45 kinds of merch, and then pay the actors starvation wages (if that) if they could get away with it. AEA is the one thing stopping commercial theatres from using actors like human ATMs.

However, AEA also covers actors working under the nonprofit model. The 501c3 model, as it applies to the arts, exists so that arts organizations can be released from the concerns of the for-profit model– continual growth, market share, and profitability that returns income to investors. It was determined, and rightfully so, that “high art,” new advances in art, and experimental art are not usually big sellers, and that if we are to have vibrant, cutting-edge art being produced in this country, or the preservation of heritage art, we need to protect them from the vagaries of the marketplace. The nonprofit model (ideally) gives companies the freedom to stop worrying about sales, market share, growth, and profitability, and instead use grants and donations to supplement income.

After a perfunctory glance at the AEA documents library, it seems to me that AEA contracts in the Bay Area aren’t much different than anywhere else, apart from being the only place in the country without a functional waiver. (I’d love to hear from some of you folks across the country if I’m wrong about that.) Our agreements are the MBAT, the BAT, and, of course, the LORT. Theatres also use the TYA agreement and the Guest Artist agreement, but primarily, the system is BAPP (our mini-waiver), MBAT, BAT, LORT. We have 5 LORT theatres in the Bay Area. The other 300 or so of us are BAT and below, so that’s what I’ll address.

This system is, of course, tiered, but not necessarily in the way you’d think. Bay Area companies can only use a BAPP for a few years before that agreement is denied to them forever, regardless of their income. The MBAT is only available to companies that use a 99-and-under theatre, and in the Bay Area, where competition for theatre space rental for a full run of 5 or 6 weeks can be fierce (before we had our own space, we used to start booking our season a year in advance), sometimes the only space available to you shuts you out of the MBAT, again, regardless of income. The BAT is internally tiered– the salaries you must pay the actors increase each year, whether your company’s income increases or not. Once you start working under the BAT, salaries are tied to TIME, not to INCOME.

By limiting the waiver and by tying salaries under the BAT to time rather than income, AEA is forcing Bay Area nonprofit theatres into a for-profit growth model, and it just doesn’t work. A nonprofit theatre’s income is in no way guaranteed to increase year by year– nor should it have to. The point of a nonprofit theatre is the art, not popularity. If we wanted to make a bunch of money, we would all be doing Annie starring Kim Kardashian and Justin Bieber.

Perfect for Miss Hannigan.

Here’s my first example: A theatre I know qualifies for the MBAT in every way except one: The theatres they rent are over 99 seats. They could afford to hire at least 5 or 6 AEA actors a season on the MBAT contract, but they’re not allowed to use it. So they can either make an all-out push to grow much larger in order to be able to afford the BAT contract and its continual increases, or they can stay non-AEA. Of course, in this economy, that kind of growth is not realistic, and why should they be forced to grow to a size that might not be sustainable for them? Solution: they only hire non-AEA actors. So that’s at least 5 or 6 AEA actors who could have been working, who instead sat home while non-AEA actors took those jobs.

I’ll use my own theatre as my next example. We’re no longer allowed to use the waiver, and we can’t afford an MBAT. The MBAT requires a weekly salary for the actor that makes the actor the highest-paid person in the room in almost every MBAT company, including the Artistic Director. We have a tiny, 59-seat theatre and we do a 4-5 show season, primarily new plays by emerging playwrights. In order to hire AEA actors regularly, we’d have to grow by about 50%. This would take years and is by no means guaranteed since we’re dedicated to accessible ticket prices, making our only avenue grants and donations. Solution: we only hire non-AEA actors. FUN FACT: I had a high-profile AEA actor call me and ask for the lead role in a show I was directing. He knew what my approach would be to the show and felt that this would be the only chance he would ever have to perform the role in that way, or perhaps even at all. I called AEA and went to bat for him, and was told no, he could not work on a waiver, and that “AEA actors need to be protected from what they want.”

But hey, now, don’t I want to pay actors? OF COURSE I DO. I would love nothing better than to pay every actor who comes through our theatre each year (about 30 per season) a weekly salary. Hell, I’d love to pay MYSELF a weekly salary. But we don’t have that kind of money.

And here’s the answer I’ve gotten repeatedly: IF YOU’VE BEEN PRODUCING FOR [X] YEARS, AND YOU DON’T MAKE ENOUGH MONEY TO AFFORD THESE CONTRACTS, YOU SHOULD JUST CLOSE YOUR DOORS. YOU DON’T DESERVE TO PRODUCE.

This is a fundamental misunderstanding of the nonprofit model.

Nonprofit theatres are not necessarily interested in a for-profit growth model. We are not necessarily interested in constantly increasing our income or our market share. Many of us are keenly aware that our work, because of its experimental nature, will never sell 500 tickets a night. Many of us do work that is specifically designed for small spaces, limiting our earned income. Many of us are devoted to accessible pricing, which limits our income. Most of us do not wish to produce work specifically designed to be popular and make money, as the commercial theatre does. Again, we do not wish to produce Annie starring Kim Kardashian and Justin Bieber.

So now you’re asking me, “OK, you’re not going to sell 500 tickets a night at $200 each. But what about those grants and donations for which the 501c3 makes you eligible?” Here’s what you need to know: grants and donations do NOT continually increase over time. In a difficult economy, they actually decrease. There are 4 kinds of contributed income: Corporate grants, foundation grants, government grants, and individual donations. Sometimes companies decide to halt all grants to the arts and shift focus to something else, or decide they want to focus on specific geographical areas, or are having a down year and decrease the amount of money they’re granting. Foundations can only grant the amount of money their endowment makes, which, as any investor knows, is not an ever-increasing amount. And don’t even look me in the face and say “government grants.” Government funding has all but evaporated. Individual donations are directly tied to the economy. You can’t donate to a nonprofit if you’ve just lost your job.

It’s impossible for nonprofit theatre companies to rely on an ever-increasing income. There is NO SUCH THING. Nonprofit theatres are not able to function on a for-profit growth model, despite what AEA thinks, and it’s AEA actors who are suffering for it.

Because nonprofit theatres aren’t growing on a for-profit model, and because our Bay Area AEA contract structure assumes that nonprofits theatres ARE growing on a for-profit model, a huge amount of Bay Area theatres are severely limited in the number of contracts they can afford or are shut out of AEA contracts entirely. Therefore, most AEA actors in the Bay Area work far less than they did when they were non-AEA, and, I would wager, make less at it as well. Sure, the one job they land pays more, but the non-AEA actor is working 7 jobs for every one job the AEA actor works. If you’re an AEA actor who’s a white man who can sing, chances are you’re working a few times a year, but if you’re a woman, forget it. Young white women show up to auditions by the wagonload, so unless you have a particular, hard-to-find skill, you are frequently easily cast around, and the company can save the 1 or 2 AEA contracts they can afford for that show for a role that’s more difficult to cast. If you’re a person of color, just getting considered can be an uphill climb at some theatres or by some directors. Because the pool of jobs available to AEA actors is much, much smaller than the ones available to non-AEA actors, actors of color are especially hard hit when they become AEA.

At the risk of repeating myself: when you’re forcing nonprofit companies into ill-fitting for-profit growth models, most companies (if not all) must limit the number of contracts they can underwrite each season. LORT theatres are favoring shows with small casts, something with which playwrights nationwide have been struggling for years now. In the Bay Area, the lion’s share of BAT and MBAT theatres are only able to hire a few AEA actors per show, casting the rest of the show nonunion, while the AEA actors who could have been playing those roles sit at home perfecting their Covenant abatement strategies.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

So what’s my solution?

Tie AEA agreements to INCOME, not to TIME or to SEATS or to anything else. That would make the relationship between AEA and nonprofit theatres realistic, and would result in more AEA actors being hired, which is good for both the theatre companies and the AEA actors. AEA contracts could be tied to a company’s income in the prior fiscal year. If it’s under X, you work under this contract, if it’s over X but under Y, you work under that contract, and so on. Income is REAL. Imagining that money undergoes mitosis and automatically grows over time is not. Imagining that a theatre space with more seats will automatically make a nonprofit theatre more money is not. Use the real income, not the imaginary income. Work out salaries that are fair when compared to the company’s income bracket. You wouldn’t need to reduce the salaries that already exist—just allow companies a more realistic set of criteria for qualifying for contracts.

Bring the Bay Area in line with the rest of the damn country and allow waivers for companies whose financials qualify, regardless of how long they’ve been producing.

Empower your membership to decide for themselves what jobs they will take. The companies who would be using a waiver are currently not using any AEA actors at all. The companies you’ve shut out of the MBAT who can’t grow to BAT are not using any AEA actors at all. Is that better for your membership, really?

And finally, stop imagining that small, nonprofit theatre companies are all sitting atop hoards of gold, arrogantly refusing to give your actors a dime while wiping their asses with hundred-dollar bills. Most of us are barely paying ourselves. Some of us don’t pay ourselves at all. And, apart from a few bad apples, almost all of us are aching to pay AEA actors– who are our friends, people we have worked with for years, people we LOVE– a living wage. Personally, I want to be able to pay ALL actors, AEA or not, a living wage.

What’s best for AEA actors? Because it can’t be struggling year after year to get any work at all while the non-AEA actors around them are working nonstop, right? And the reason that happens isn’t because producers are dicks. It’s because we’re desperately trying to keep the doors open, and we only have so much to allocate for personnel after donations have fallen off and one of our major granting orgs closed their grants for the arts completely, and we did two new plays last year that were critical successes but didn’t sell well, and because we want to keep ticket prices affordable so our audience can stay diverse. And because we’re not working under a profit-driven growth model. And we don’t want to do The Facts of Life: The Musical! with Taylor Swift as Blair, Beyonce as Tootie, and Seth McFarlane as Mrs. Garrett. OK, maybe a little BUT THAT’S NOT MY POINT.

My point is: There has to be a better way, for ALL of us.

UPDATE: There are indeed several other places across the country without a waiver. I feel your pain, Salt Lake City and Las Vegas (and anyone else out there). I feel your pain.

SECOND UPDATE: I’m thrilled with the conversations this has started. I’m even more thrilled that we seem to be thinking of ways to come together to work within the confines of the financial reality of the nonprofit theatre world.

Comments for this article are now closed. I’ll be posting a follow-up article soon!